By Nicholas Dufault

There have been many concerns this year with potato seed management related to the Blackleg problem, caused by Dickeya dianthicola, in the northern seed producing states (Figure 1). Seed borne diseases, such as blackleg, can go unnoticed until it is too late. Paying close attention to the seed from production to planting can help reduce the impact of these devastating pathogens. This has led to the general question, “What can I do to monitor for Blackleg and other seed borne disease issues?”

In general, there are 3 major steps to follow when monitoring potato seed:

- Potato seed management starts with a seed certification. All U.S. seed producers should have a seed certification program that provides a North American Certified Seed Potato Health Certificate. These programs produce high quality seed stock, but it is important to realize it is not disease free. It is impossible to inspect every plant or seed, but through the use of multiple samples, and an understanding of the seed grower’s field history, these programs are able to limit the spread of many microbes. Buying only certified seed is one of the best ways to start reducing seed borne issues.

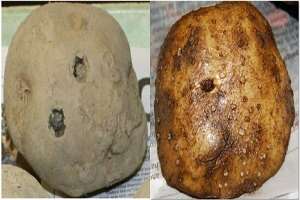

- The next step in the process is to evaluate the shipment before accepting it. This can be done by visually inspecting the lot in the shipment container or by taking samples (using a 5 gallon bucket) from various areas and examining the seed closely. These inspections are done to look for external damage to the tubers, such as bruising, splitting or wounds (Figure 2). The symptoms can indicate infection points for storage pathogens and could be a good place to sample to see if further pest damage exists. There are many pathogens that resemble physical damage to tubers (e.g. powdery scab) (Figure 2 and 3), so if there is uncertainty about a symptom contact your local extension office with questions.

Figure 2:Damage that can occur from wounding on the left and from excessive moisture leading to enlarged lenticels on the right.

Figure 3: Damage from fungal pathogens with an example of Fusarium dry rot on the left and powdery scab on the right.

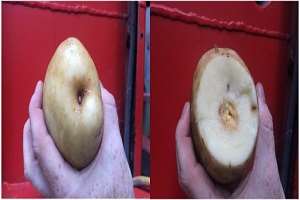

- The last step is to monitor the seed as it is being cut. In many cases it is not possible to see the presence of a problem externally (Figure 4), but when cutting the seed you may notice internal disease symptoms (Figures 3, 4 and 5). Periodic cleaning and sterilizing of the cutting equipment is a useful tool for managing disease spread in seeds. However, once an internal seed problem is noticed, especially soft-rotting tissue, it is vital to stop all cutting until the blade can be sterilized. Many pathogens can be transmitted by unclean cutting blades, and this is one major path in which blackleg can spread through a seed lot. Monitoring seed cutting is critical to limiting potato disease issues related to seed.

Figure 4: The blackleg pathogen, Dickeya dianthicola, can infect daughter tubers and go relatively unnoticed in seed pieces until cutting. (Photo courtesy of Clay Pederson)

Figure 5: An example of bacterial soft rot in a potato tuber on the left and the physiological disorder internal heat necrosis on the right with some bruising also present on the edge.

No matter what we do for seed management, there will always be some disease or pest issue that will go unnoticed. The goal of any seed monitoring program is not to eliminate an issue but rather keep it at a level that minimizes yield losses and pathogen spread. Seed monitoring is only one step in an integrated management program. Other integrated management techniques (e.g. seed treatments and in-season disease monitoring) are still need to produce a quality crop.

Source: ufl.edu