By Romulo Lollato

Wheat and Forages Specialist

The extent of possible winter damage to the developing wheat crop due to low temperatures will depend on several variables, including:

- Extent and duration of low temperatures

- Crop development

- Soil temperature

- Soil moisture

- Snow cover

- Soil residue cover

- Wind speed

- Stand density

- Temperature gradients in the field

Minimum air temperatures and their duration are the leading factors in any possible winter injury. However, it is important to remember that the crown is protected by the soil during this stage, so factors other than air temperature also need to be considered. For instance, crown insulation by the soil (influenced by seed-to-soil contact at sowing and sowing depth), crown root development, above-ground crop development, soil temperature, soil moisture, snow cover, crop residue, and how well the crop acclimated during the fall, will all influence the crop’s response to below-freezing temperatures at this stage.

What level of cold can the wheat crop withstand at this stage?

Wheat needs at least 4-5 leaves and 1-2 tillers prior to winter dormancy for maximum cold tolerance. In this situation, wheat can withstand air temperatures of -5 to -10 degrees F for a couple hours without significant risk of winterkill (Figure 1) as long as temperatures at the crown level do not reach single digits.

Figure 1. Temperatures that cause freeze injury to winter wheat at different growth stages. Maximum resistance to cold temperatures occur between mid-December and early-February.

Wheat that has fewer tillers and leaves will be more susceptible to winter kill, which unfortunately is the situation for the majority of the Kansas wheat crop during the 2017-18 season. During the fall of 2017, wheat sowing was delayed for about 60-80% of the Kansas crop due to early October precipitation. Therefore, the crop is behind in development as compared to the historical average. Many fields in north central Kansas had sowing delayed even further as producers had to finish a summer crop harvest prior to sowing wheat. It was not uncommon for producers in that region to sow wheat in the last week of October or after the first of November. The crop likely did not have enough time to tiller during the fall (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Upper panels reflect early October sown field (left) and plant (right) and lower panels reflect a wheat field (left) and plant (right) sown in the last ten days of October.

How cold did it get?

Minimum air temperatures reached very low levels on New Year’s Day across Kansas, with temperatures as low as -16 degrees F recorded in the north central and northeast portions of the state (Figure 3). Parts of southwest Kansas, central, and north central Kansas had minimum temperatures reaching values lower than -5 degrees F which could result in damage to the crop. While most of the state was exposed to minimum temperatures below 0 degrees F for the week ending on January 2, 2018, potential damage should be restricted to areas where minimum temperatures reached values below -5 to -10 degrees F.

Figure 3. Lowest Minimum Air Temperatures, December 27, 2071 – January 2, 2018.

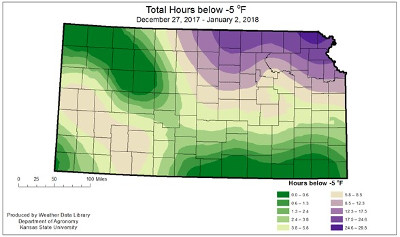

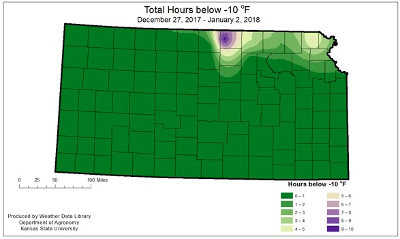

How long were these cold temperatures sustained?

As mentioned earlier, the risk of freeze damage to wheat is a function of the minimum temperature and duration of time spent at potentially damaging temperatures. During the week ending on January 2, 2018, the number of hours below -5 and -10 degrees F varied according to geographical location within Kansas (Figure 4). The majority of the wheat growing region had anywhere between 4 to 24 hours below -5 degrees F and less than 1 hour below -10 degrees F, with exception of north central Kansas. Counties in the north central and northeast portions of the state were exposed to as many as 30 hours below -5 degrees F and approximately 10 hours below -10 degrees F. The greatest risk of winterkill will be areas where temperatures were sustained below -10 degrees F for long periods of time, but areas with a long period of time below -5 degrees F could also sustain damage.

Figure 4. Total number of hours below -5 degrees F (upper panel) and -10 degrees F (lower panel), December 27, 2071 – January 2, 2018.

Soil temperatures

As freeze damage potential is a result of many interacting variables, evaluating only air temperatures may not completely reflect the conditions experienced by the wheat crop. In this situation, soil temperatures can help determine the extent of the cold stress at crown level.

While air temperatures reached critical levels for foliar tissue damage and in parts of the state, winterkill, soil temperatures at 2-inch and 4-inch depth were above 27 degrees F in northwest Kansas, and in most cases between 30-35 degrees F in other regions of the state (Figure 5). The lowest recorded soil temperature was 19 degrees F at the 2-inch depth near Scandia in north central Kansas. During the fall, most of the wheat winterkill occurs when temperatures reach single digits at the crown level. Higher soil temperatures may have helped buffer the cold air temperatures, thus minimizing possible injury to the wheat crop.

Figure 5. Soil temperatures measured at 1:15 pm on January 4th for the 2-inch/4-inch depth.

Soil moisture

North central Kansas recorded the lowest temperatures for a longer period of time compared to other regions of Kansas during the week ending on January 2. In addition to the low temperatures, this area of Kansas is also experiencing abnormally dry conditions due to no significant precipitation for weeks (Figure 6). The lack of soil moisture decreases the capacity of the soil to buffer temperature changes. As a result, a dry soil will cool down faster than a moist soil, increasing the chances of lower temperatures at the crown level and subsequent winter injury.

Figure 6. Kansas drought conditions as of January 4, 2018. Map developed by United States Drought Monitor (http://droughtmonitor.unl.edu).

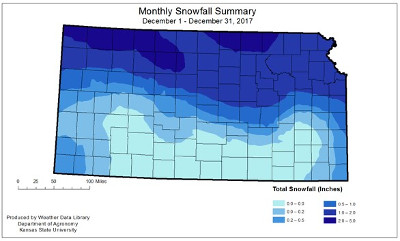

Snow cover

Another factor affecting the potential for winterkill to the wheat crop is the amount of snow cover when low temperatures occurred. Snow can act as a buffer to cold air temperatures. If a minimum of 1-2 inches of snow is present on top of the wheat canopy, temperatures at the soil level should be sustained close to ~32 degree F. However, if less snow is present or if windy conditions removed the snow from the wheat canopy, the buffering effect might not occur. Figure 7 shows the total snowfall accumulated in two events prior to the occurrence of the low temperatures on New Year’s Day (mostly accumulated between December 24th and 26th). Anywhere from 0 to 5 inches of snow were accumulated in Kansas, with the largest amounts measured in parts of north central and northwest Kansas (Figure 7). The majority of Kansas, where colder temperatures occurred (north central), had some level of snow coverage, ranging from 1 to 5 inches. If the snow was present at the wheat fields at the time low temperatures occurred, it likely helped the crop withstand the low temperatures measured.

Figure 7. Monthly snowfall summary for December 2017. The majority of the measured snowfall occurred in two events (December 24th and 26th), a few days prior to the onset of the coldest temperatures measured.

Summary

Air temperatures measured during New Year’s Day were cold enough to harm the wheat crop in many parts of the state, especially north central Kansas where temperatures where sustained below -10 degrees F for up to 10 hours. The effects of the cold temperatures could be magnified by dry soil conditions and poor fall development due to late sowing across the state.

Potential for winterkill exists, especially in north central Kansas (very cold temperatures for a long period of time), or in other areas of the state where air temperatures were sustained below -5 degrees F for several hours, worsened by a dry topsoil. On the bright side, soil temperatures never reaching single digits at 2 inches across the entire state, and snow cover up to 5 inches in some areas could have helped winter wheat survival.

It is difficult to truly assess the extent of the damage at this point. Thus, producers should not take any immediate action. While foliage damage will be apparent a few days after the cold event, the first apparent sign of freeze injury being leaf dieback and senescence, symptoms of winterkill will only be apparent at spring greenup. This is when the crop starts to take up water and nutrients for spring growth. Damaged leaves will appear burned back and dead, but that is not a problem as long as newly emerging leaves in the spring are green. Provided that the crown is not damaged, the wheat will recover from this foliar damage in the spring with possibly little yield loss. If damage to the crown occurred, the crop will not greenup in the spring or will greenup for a short period of time using existing resources, and perish shortly after. In any case, we will only be able to assess the true extent of the damage at spring greenup.