By Mary Barbercheck

Predatory insects and spiders control insect pests and slugs, reduce crop damage in transition to organic crop production

The growing demand for organic livestock, poultry and eggs is driving Pennsylvania’s #2 ranking for organic sales in the U.S., following #1 ranked California. All organically-produced animals require 100% organic feed and forages. The U.S. organic livestock and poultry production industries currently cannot meet the need for organic feed and forage with domestically-produced grains, with the result that the majority of organic feed grains are imported from several countries, including India, Turkey, Romania, and Ukraine. The shortage of domestic organic feed grains represents an opportunity for U.S. corn and soybean growers as there is a considerable price premium offered for organic compared with conventionally-produced feed grains. To meet demand, we need more domestic acreage in organic production but transition to organic from conventional management can be risky. It takes three years of management without transgenic varieties or synthetic inputs, including pesticides and fertilizers, before land can be certified and harvests can be sold as organic. Because of the restrictions on crop varieties and pest management inputs, organic growers rely largely on cultural practices and tillage for pest management. Many growers are concerned that heavy reliance on tillage may be damaging to their soil.

A group of researchers in the College of Agricultural Sciences at Penn State have focused their research on reducing tillage in organic systems while managing pests to help reduce risk during transition. To accomplish tillage reduction, we are investigating “rotational tillage” -- a system in which winter cover crops are rotated with annual grain or forage crops, and tillage only occurs on a semi-regular basis. The winter cover crops may be terminated with a roller-crimper, which rolls the cover crop to the ground while crimping the stems. The rolled cover crop creates a mulch layer at the soil surface into which the subsequent cash crop is no-till planted.

Winter cover crops can provide habitat for beneficial predatory insects like ground beetles (photo), and spiders, but may also provide habitat for early season pests, like black cutworm, that can reduce early-season stand establishment. Our research has focused on the relationship between the effects of cover crop mulch on predators, predation, and early season crop damage, especially in corn during the transition. Entomology graduate student, Ariel Rivers, conducted a three-year experiment in the Reduced-tillage Organic Systems Experiment (ROSE) at the Russell E. Larson Agricultural Research Center in Rock Springs, PA. The rotation, including cover crops, was corn for silage, cereal rye (Secale cereale L.), soybean, winter wheat, followed by a biculture of hairy vetch (Vicia villosa Roth) and triticale (× Triticosecale Wittmack), followed by corn for silage. The cover crops were planted into ground prepared with a moldboard plow in the fall, with a seeding rate of 30 lbs/ac each of hairy vetch and triticale in plots that would be followed by corn, and 168 lbs/ac cereal rye in plots that would be followed by soybean. In the spring, we managed the cover crops with a roller-crimper just before or at the time of planting of corn or soybean, and then rolled a second time shortly after planting to improve cover crop kill. Corn and soybean were no-till planted into the rolled cover crop at rates of 34,000 and 225,000 seeds per acre, respectively. All seed was organic or untreated, conventionally-bred varieties.

Annually, we measured the community of predatory insects and spiders with pitfall traps, which mainly capture insects and other organisms associated with the soil, and estimated predation rates by placing traps baited with waxworms as prey in the field at the same time. We also counted pest caterpillars and slugs on the soil surface in defined areas to estimate early-season pest numbers. At V4 in corn and V1 in soybean, we assessed plant population and damage from insects and slugs.

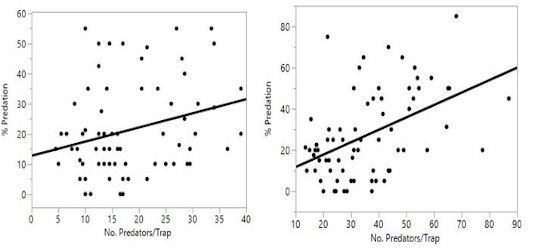

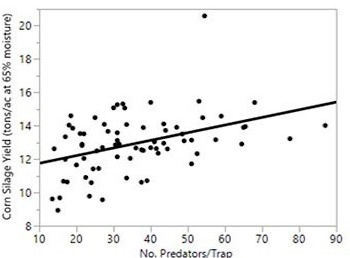

During the three-year experiment, we captured nearly 18,000 insects and spiders in pitfall traps. The most abundant predators were spiders (22% of all captures) and ground beetles (8% of all captures). Other important predator groups were rove beetles (6%), daddy-long-legs (4%), and ants (3%). Both the number of predators and the rate of predation on the waxworm baits increased over the 3-year transition in both the rolled hairy vetch-triticale mix and the rolled cereal rye. In both cover crops, the number of predators was positively correlated with the proportion of damaged waxworms during all years of the experiment, with predation increasing with number of predators (Figure 1). The number of pest caterpillars and slugs were greater in rolled hairy vetch-triticale than in rolled cereal rye. The number of soybean plants in the rolled cereal rye cover crop was positively correlated with the number of predators and the proportion of damaged soybean plants was negatively related to predator numbers. In the hairy vetch-triticale, the number of predators were negatively related to the number of pest caterpillars. Lower density of slugs in the final two years of the experiment correlated with number predators in both rolled cereal rye and rolled hairy vetch-triticale. Corn silage yield was positively related to number of predators (Figure 2), but there was no relationship between number of predators and soybean yield.

Figure 1. Relationship between numbers of predators captured in pitfall traps and predation on waxworm baits on the soil surface in corn planted into rolled hairy vetch-triticale (left) and in soybeans planted into rolled cereal rye (right).

Figure 2. Relationship between predator numbers and silage corn yield during the three-year transition to organic production.

These results indicate that regardless of which of the crop species a predator resides, predatory arthropods can contribute to biological control, an important ecosystem service. Early-season plant damage from cutworms decreased with time in organic management and further suggests that the increasing abundance of predators may have contributed to increased biological control over the three-year transition period. The increase in predatory arthropods and the correlations between predators and predation, lower slug density, higher soybean populations, and higher corn silage yield indicate an important positive response of predators to the organic reduced-tillage system. That is, as pests increase, predators and predation increases, resulting in lower plant damage and sometimes greater yield. Overall, early-season crop damage from pests was minor and not related to corn or soybean yields in this experiment. According to our results, length of time in organic management was the greatest predictor of predator numbers and predation rate, and was correlated with lower plant-feeding insect and slug densities and cash crop damage. These results suggest that insect pests should not be a limiting factor in transitioning systems that reduce tillage by no-till planting cash crops into a rolled cover crop, but this remains to be tested on Pennsylvania farms.

Source : psu.edu