By David Lowenstein

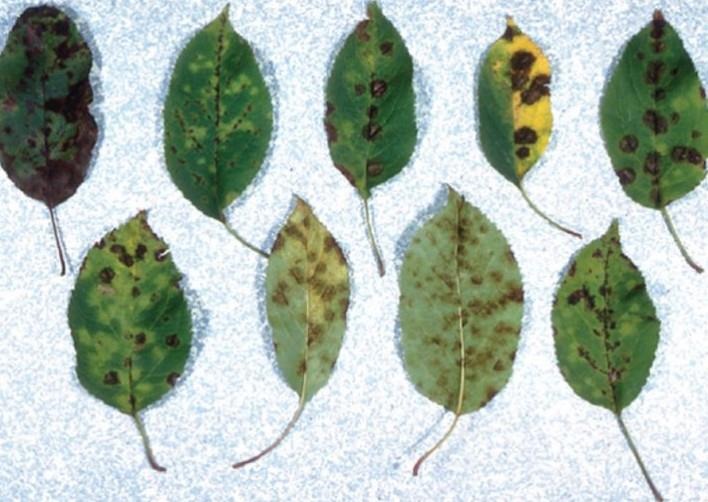

Photo 1. Apple scab on leaves. Photo from MSU Extension.

Apples are one of the most popular fruits consumed by people of all ages. They come in a wide variety of colors, sizes, tastes and are used in many products as a primary and secondary ingredient. What makes them even more desirable is that apple trees are cold hardy and relatively easy to grow in your backyard. Unfortunately, apple trees are also susceptible to a variety of diseases including apple scab.

What is apple scab?

Apple scab is a fungus, Venturia inaequalis, affecting most apple varieties. In spring, the fungus spreads from overwintered spores of infected leaves to new leaves through wind and splashing from rain. The risk of scab is greater in years with wet springs. As the spores reproduce within the plant, circular brown to black lesions develop several weeks later on the leaves (Photo 1). Areas around the lesions will sometimes lighten in color or turn yellow. The size of lesions can range from very small to large enough to cause early leaf drop and unmarketable fruit. In more severe cases, the tree may drop its leaves in July or August.

In addition to lesions on the leaves, scab-infected trees will produce brown and corky apple fruits (Photo 2).

Photo 2. Raised blotches on apples that indicate scab infection. Photo by Bill Shane, MSU Extension.

Photo 2. Raised blotches on apples that indicate scab infection. Photo by Bill Shane, MSU Extension.Preventing scab with fungicides

Trees that have apple scab can continue to produce new leaves in the following season. Michigan residents with crabapple trees can do nothing, as the damage will only be cosmetic. Fall removal of scab-infected leaves from the orchard floor is essential to reduce the risk of scab transmission in future seasons.

Applying fungicides to the leaves is one preventative treatment. To achieve a good yield of fruits without scab, fungicide applications every 10-14 days are required from when a half inch of the green tissue has grown (green tip) through the week after petal fall. Captan and Myclobutanil are two fungicides that home orchardists can apply. If your tree already has apple scab, it is too late to apply a fungicide that will eradicate the disease.

Michigan State University Extension always advises that gardeners who choose to use chemicals must read the product label before application and to confirm that it is registered for use in the location they plan to spray.

Preventing scab with resistant varieties

In recent years, an increasing number of scab-immune apples have been developed by plant breeders from across the United States and elsewhere. Some selections have resulted from cross breeding and others from natural mutations in the field. These resistant options are great news for backyard orchardists. Fewer sprays will result in a cost savings and protecting the environment; a win-win situation. In addition, partial or total resistance to diseases fits well into organic management practices for organic growers.

Several commonly grown varieties such as Cortland, McIntosh and Honeygold have a high susceptibility to scab. A list of apple varieties and their susceptibility to scab is available on a Michigan State University Extension resource on scab susceptibility by variety. Another excellent resource is “Apple scab of apples and crabapples” from the University of Minnesota Extension.

Some popular, scab-immune apple varieties for the Michigan home orchardist to consider include:

- Pristine: A very early, large green or yellow apple (pies or sauce).

- Redfree: An early, medium-sized, red apple (fresh, pies or sauce).

- Macfree: Early season, McIntosh-type of apple (fresh or sauce).

- Freedom: Large fruit that is also resistant to cedar apple rust and fire blight. Can bruise easily (cooking and pies).

- Jonafree: Similar to Jonathan with pale-yellow flesh (fresh).

- Liberty: Fall apple, high quality, red apple with crisp flavor (fresh or cooking).

- Novaspy: Spy-type of fall apple (pies and other cooking).

- Enterprise: Very late fall apple with uniform red color (fresh or cooking).

- Goldrush: Very late fall apple with uniform yellow color (fresh or cooking).

- Candycrisp: Very late fall apple with green color and very sweet flavor (fresh or cooking).

- Crimson crisp: Fall apple with medium to dark red fruit (fresh).

Be aware that varieties resistant to apple scab might still be susceptible to other diseases and some fungicide and bactericide sprays might still be necessary. A list of cultivar susceptibility to other common apple diseases can be found in “Disease Susceptibility of Common Apple Cultivars” from Purdue University Extension. Also, consider the rootstock in your overall size of tree. A more dwarfing tree will allow for easier spray coverage and lend to the overall success of your backyard apple endeavor.

Source : msu.edu