By Michelle Arnold

Which cows in your herd are consistently making you money? Every year, the cow-calf producer needs to critically evaluate each animal in the herd and decide if she is paying her upkeep. Open cows (those that are not pregnant) at the end of breeding season obviously are high on the cull list. With variable costs running $400-$500 per year per head and an additional $100-$300 in fixed costs, keeping open cows is difficult to justify financially. Beyond pregnancy status, what other variables are important to evaluate? Structural soundness, body condition score, age, annual performance, and disposition are significant factors to consider when developing a culling order specifically for your farm. This culling order is essentially a ranking of the cow traits you consider most important for a cow to be productive on your farming operation. Culling is exceptionally important during times of drought or a year with marginal hay production as you may be forced to cull deeper to manage through a challenging season. However, there may be times to consider keeping more replacement heifers and letting older cows go, such as when many in the herd are getting older and the heifers have good genetic potential to perform. To begin, it is best to think about which animals in the herd have the least chance of being productive over the long term or are farthest away from being productive. Equally important are factors such as disposition and phenotype (color, size) that affect the marketability of offspring. The following is a list of factors to carefully consider when deciding who to cull this year.

- Disposition – A cow’s attitude is an important consideration in any cattle operation. Bad behavior has both a genetic component and is also learned behavior by calves at an early age. Mean, nervous, “high strung” cattle are dangerous to people, damage facilities, tear up fences and make gathering and working cattle difficult at best. Remember a good cow can be protective of her calf without being dangerous and destructive.

- Pregnancy Status – A cow should produce a calf at least once a year and the sale of that calf needs to pay her way. Diagnosing a cow as “open” (not pregnant) is as simple as having a veterinarian palpate for pregnancy at least 40 days either after breeding or after the bull is removed. A simple, inexpensive blood test can also be used 28 days post-breeding to determine pregnancy status. If many cows are found open at pregnancy check, work with your veterinarian to determine if reproductive disease, poor nutrition, bull infertility or inability to conceive was the cause. Remember cows that calve late in the season have fewer opportunities to breed back in a controlled (for example, 90 day) breeding season. Summer heat and fescue toxicosis can be important contributors to low conception rates.

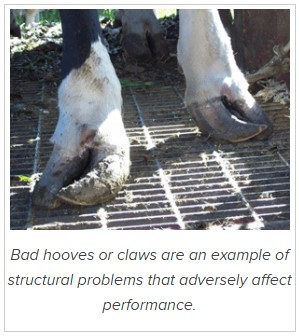

- Structural Soundness – Bad hooves or claws, lameness due to hip/knee injury, eye problems, and poor udder conformation are all examples of structural problems that adversely affect performance. Good feet and legs are essential for weight maintenance, breeding, calving, self-defense, and raising a calf. The udder should be firmly attached with a level floor and high enough that newborn calves can easily find and latch onto teats. Cows with blind or light quarters, funnel or balloon shaped teats, or any history of mastitis are strong candidates for culling.

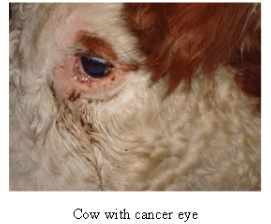

- Cows with chronic conditions that will not improve such as progressive weight loss, early cases of cancer eye, repeated episodes of vaginal prolapse during pregnancy, and extreme sensitivity to the effects of fescue toxicosis should be removed from the herd as soon as the calf is weaned. Cows with confirmed disease conditions such as Johne’s disease, bovine lymphoma, or advanced cancer eye should not be sold to a commercial market. The most common reasons for carcass condemnation at slaughter include emaciation, lymphoma, peritonitis, cancer eye, blood poisoning, bruising, and other types of cancers.

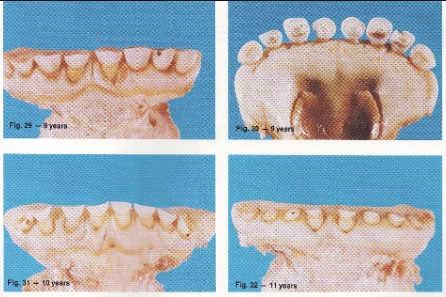

- Age – Cows are considered most productive between 4-9 years of age. The size and shape of the teeth can be used to assess age but always evaluate them in light of the diet. Cows that eat gritty or sandy feeds and forages have increased tooth wear beyond their years. Regardless, cows with badly worn or missing teeth will have a hard time maintaining body condition. Remember, older cattle die of natural causes, too.

- Poor Performance – Record keeping is an invaluable tool for evaluating performance. Readable visual tags on both the cow and calf allow you to match calf sale weights to the dams and identify cows that did not produce a calf. Inferior genetics and poor milk production produce lightweight calves that do not grow well. An overweight cow or large framed cow with a small calf that doesn’t gain weight usually means the cow is not producing much milk. Sick baby calves may be an indication of poor quality colostrum and poor mothering ability.

- Phenotype – Cows that do not “fit” the herd because of external features such as unusual breed, size, muscling and color are candidates for culling. These challenges may be overcome to some degree by choice of sire to balance out the unwanted traits. Remember that buyers of commercial calves look for uniformity in color, weight, and frame in a set of calves and will pay a premium price for it.

- The last ones to go – Hopefully culling will never have to go this deep in your herd. Bred cows over 9 years old, replacement heifers (especially those that did not breed in the first 30 days), and bred cows 3-9 years old should be the last sold. Thin cows that conceive late in the breeding season should go first.

Since 20% of gross receipts in a typical cow-calf operation come from the sale of cull animals, pay attention to price seasonality and body condition score before sending these animals to market. Prices are historically highest in spring and lowest in late fall/early winter when spring born calves are weaned and many culls are sent to market. Adding weight and body condition to culls is an opportunity to increase profitability but can be expensive. Work with a nutritionist to come up with realistic cost projections before feeding cull cattle for a long period of time.

When it comes to making decisions on who to cull, remember to consider functionality in your environment. Is she an “easy keeper”? Does she keep flesh and condition and raise a good calf, even when feed and forage is limited? On the opposite side, does she give too much milk or is her frame size so large that you can’t keep weight on her, even when pasture is plentiful? Is her pelvis so small and tight that calving is a problem and will be a problem in her offspring? Functionality leads to longevity and improved efficiency. By retaining more young cows in the herd, you can decrease the number of replacement heifers needed each year and cull cows that are only marginally profitable. Young cows also increase in value as they mature because the body weight of the cow and her calf’s weaning weight will continue to increase until approximately 5 years of age. Longevity will also be improved through crossbreeding because hybrid vigor adds essentially 1.3 years of productivity or one more calf per cow. If considering buying heifers, UK has a decision support tool available at http://www.uky.edu/Ag/AgEcon/pubs/BredHeifer.xlsx to help understand how to evaluate the price in your specific circumstances.

In summary, a herd of easy-keeping, efficient cows is possible through rigorous culling and careful selection of replacements. Match your genetics to your management and environment for maximum efficiency, longevity, and ultimately, maximum enjoyment of cattle production.

Cull Cow Language

- Breakers (75-80% lean)- Highest conditioned cull cows (BCS ≥ 7), excellent dressing percentages

- Boners or “boning utility” (80-85% lean)- Moderately conditioned (BCS 5-7), well-nourished commercial beef cows (usually highest price cull)

- Leans (85-90%)- Lower BCS (1-4), lower dressing percentages, susceptible to bruising during transport and expect more trim loss. Moving cows from lean to boner status can usually be done efficiently

Source: osu.edu