The discovery of a molecular “emergency mode” could pave the way for climate-resilient crops and improved early-season growth. Photo of wheat sprouts covered in a frost by ligora via Getty Images.

One things for sure—weather happens. When a sudden cold snap hits a farm, it can destroy seedlings slow growth. It can make the season's growth "iffy" going forward.

But like a ray of sunshine, results from a new study offer farmers hope.

Scientists have discovered how plants are able to activate an internal “emergency mode” which allows them to survive these harsh conditions—opening doors to breeding crops that thrive despite climate volatility.

Scientists from South Korea's Chonnam National University (CNU) have learned how plants are able to activate a hidden genetic “switch” to enable them to survive when there are sudden drops in temperature.

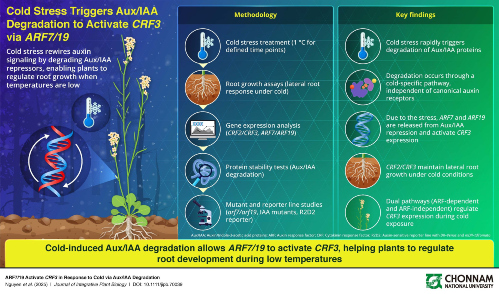

The team's findings were published in the Journal of Integrative Plant Biology, and show that when a plant is affected by cold stress, it triggers a rapid breakdown of auxin/indole acetic acid (Aux/IAA) proteins—repressors that normally block growth-related genes. Once these proteins degrade, regulators ARF7 and ARF19 are freed to activate CRF3, a master gene that reshapes root architecture for survival.

“Cold stress doesn’t simply slow plant growth—it actively rewires hormone signaling to adapt root development,” said Professor Jungmook Kim, who led the study.

The research also found that cytokinin signaling kicks in under cold conditions to activate CRF2, which works alongside CRF3. Together, these genes integrate environmental stress signals with internal hormone pathways, fine-tuning lateral root initiation. This convergence of auxin and cytokinin pathways forms a unified cold-response module.

“Plants survive because they integrate external stress with internal developmental programs,” added Professor Kim. “We have identified one of the key switches enabling that integration.”

The discovery opens new opportunities for crop improvement. By enhancing CRF2/CRF3 signaling or by stabilizing the ARF activity through targeted degradation of Aux/IAAs, plant breeders could develop crop varieties that will be able to maintain their root growth in cold soils.

Crops like this would be able to improve uipon their individual nutrient uptake, reduce the amount of fertilizer needed, and support a more sustainable environment.

The study also points to the potential of biostimulants or synthetic molecules in providing protection for seedlings during unexpected cold spells.

Researchers believe this molecular pathway could underpin precision breeding and CRISPR-based engineering of climate-resilient crops over the next decade.