Be prepared to handle and transport cattle appropriately in cold weather. The cold, wet and wind of winter weather present a different set of challenges.

Winter weather if finally arriving and when it gets here for good we need to be prepared to handle and transport cattle appropriately. The heat of summer can be a challenge but the cold, wet and wind of winter and early spring can cause headaches that can’t be matched.

Winter stress factors may include temperature, wind, rain, snow, mud, feed quality, feed quantity, body condition, adaptation, and perhaps others. Cattle can be amazingly tolerant of cold conditions, but there are certain times when the manager needs to be thinking about what can be done to mitigate stressful cold conditions. This requires some knowledge of the science involved and a certain amount of common sense and experience.

Research refers to the lower critical temperature (LCT) when describing the ability of cattle to withstand cold conditions. The LCT is the temperature at which maintenance requirements increase to the point where animal performance is negatively affected. Various sources put this temperature between 18-20 degrees F. However, a fact sheet from NDSU states that after adaptation, mature beef cows in good body condition during the middle third of gestation may have an LCT as low as minus 6 F during dry, calm conditions.

Critical temperatures for beef cattle are determined in part by the condition of the coat. Below the critical temperature, livestock must expend more energy in order to keep warm.

Coat Description Critical Temperature

Summer coat or wet 59 degrees F

Fall coat 45 degrees F

Winter coat 32 degrees F

Heavy winter coat 18 degrees F

Adapted from D.R. Ames, Kansas State University.

When the animal has a lighter coat the LCT goes up. If the cow has a summer coat or is wet, the LCT is around 60 F. Of course we wouldn’t normally expect a cow with a summer coat to be subjected to winter. Early blizzards out west, where we often see a number of dead animals, adversely affect cattle whose coats were not at a winter level. Cold rains can happen in the winter and a winter coat is almost useless when wet. When the coat is wet it loses the insulation factor that is essentially air trapped between hair fibers. Most stockmen know that an animal is usually better off in snow rather than cold rain.

Several sources concur that for every degree below the LCT a cow’s energy (TDN) intake increases by one percent. Basically the animal needs more energy to maintain itself.

What can a cattle manager do to make sure his/her animals are not subjected to unnecessary cold stress?

Protection from wind is obvious. Wind chill can worsen stress from a cold rain. A well-ventilated building, stack of big bales, woods, brush, fencerows, and hollows are all potential windbreaks.

Reduce muddy conditions to every extent possible. This can be difficult, especially in March. Mud has pretty much the same effect as rain in reducing insulation from the cattle’s hair. Use bedding to help keep cattle clean and to provide insulation from mud or frozen ground. Rotate hay feeding areas if possible. In many situations mud can’t be fully avoided, but at least try to establish an area where cattle can lay down that is able to be bedded and dry. If you need assistance with mitigating muddy, heavy use areas, contact USDA-NRCS to discuss ideas on what can be done to improve your situation.

Feeding programs may need to be tweaked in prolonged cold conditions. Be prepared for cattle to eat more – cows normally consuming 2.5% of their bodyweight in hay may increase to 3.5%. Provide higher quality forage if available. Digestibility and energy levels in the forage are the key things to focus on. Higher energy forage will help the cattle deal with increased energy expenditure.

Supplementing cattle with grain or by-products is another strategy, especially if the only forage available is low quality. A few pounds of grain may be all it takes, but discuss this with a nutritionist to make sure you don’t overfeed or underfeed the supplement.

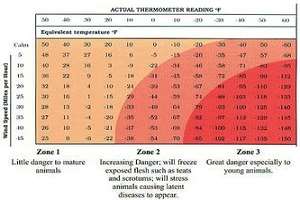

One area of concern that we sometimes forget about is transporting animals in cold weather. The following chart shows the effect of wind speed when added to the temperature. There may be no wind but the animals on your trailer heading off to the stockyards, or starting a 3 hour drive to Harrisburg for the PA Farm Show, only know your truck is moving 60 miles per hour and it’s really cold back there.

Looking at the chart, if its 20 degrees F and the wind is 40 mph, the wind chill is -21 F. If you haven’t done something to block the airflow in your trailer, those animals are having a pretty chilly ride.

Remember, if your cattle are wet and you are transporting them in cold weather, the danger will be even greater. It will be critical to get your animals to the destination as quickly as possible.

Cold weather is stressful for both cattle and cattle producers. The use of a little common sense and planning will go a long way to make this winter a less stressful time.

Source: psu.edu