Should you increase your seeding rates of spring wheat as seeding is delayed yet again? The short answer is 'Yes, you probably should. There are two approaches to determining how much seed you should commit to the seedbed. The physiological underpinnings and thus reasons for doing so are the same in both approaches. The suggested seeding rates that each approach yields do not differ that much but are reported a little differently.

To understand why you need to increase your seeding rate, I refer you to the post I posted earlier today. As seeding is delayed, the crop will go through its paces faster and reach each developmental stage sooner. This includes the initiation of tillers. Later seeding will result in fewer tillers being initiated and increasing your seeding will offset the loss of tillers and thereby partially offset the yield loss of the delayed seeding.

The conventional rule of thumb was to increase the seeding rate enough that the initial stand is increased by 1 plant per square foot or about 3.5% for each week seeding is delayed past the optimum planting window. To attain that increase in the initial stand you need to increase your seeding rate not just by 3.5% but by 5% in the first week and at least 10% in the second week. The reason for this is that stand losses (viable seed that does not emerge as a seedling) increase as seeding rates are increased. My research in the mid-nineties suggested that the optimum and maximum seeding rates for each variety somewhat differed and there was not much benefit to going higher than an initial stand of 34 to 36 plants/ft2.

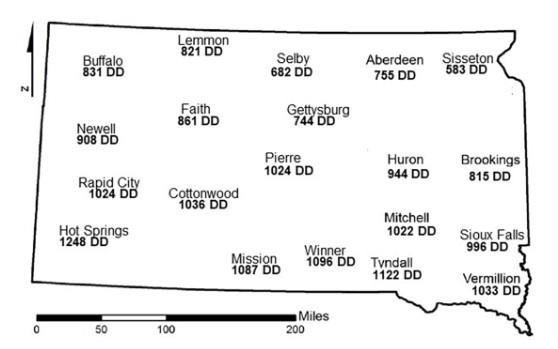

A few years ago J Stanley's Ph.D. research revisited the work I had done in the early nineties. He took a different approach by not looking at the initial stand but the number of live seeds per acre that maximized grain yield in a given environment. His dataset included much larger geography that spanned from southern Minnesota to western North Dakota. His decision key ( Figure 1) takes the expected yield, straw strength, and tillering capacity of the variety into account.

At first glance, the suggested seeding rates run counter to the older rules. The lower yield potential category included more environments where water was the first rate-limiting factor not delayed planting. When looking at the moderate and high-yielding environments, the suggested seeding rates come much closer to the older rules when considering that stand loss increases as seeding rates are increased. Later planting, for example, will generally result in a shorter crop that is less prone to lodging, thereby allowing you to increase the seeding rates more if your variety is more prone to lodging. A seeding rate of 1.6 million live seed yields about 33 plants per square foot if you assume about 10% stand loss.

|

| Figure 1 - Decision tree for determining the optimum seeding rate for different varieties and expected yield potential in Minnesota and North Dakota. |

Source : umn.edu