By Rosemary Brandt

Corn is a colossal grain in the global food and feed chain, with the U.S. producing roughly 30% of the world's supply, or nearly 278 million metric tons in the 2024–25 growing season alone. But its journey from wild grass to staple crop began in central Mexico with teosinte (from the Nahuatl word "teocintli," meaning "sacred corn"). Over thousands of years, domestication and selective breeding transformed teosinte into the corn we enjoy at backyard barbecues today.

Now, researchers are returning to this wild crop relative to investigate traits that may have inadvertently been left behind, traits that influence how roots interact with soil microbes and cycle nitrogen.

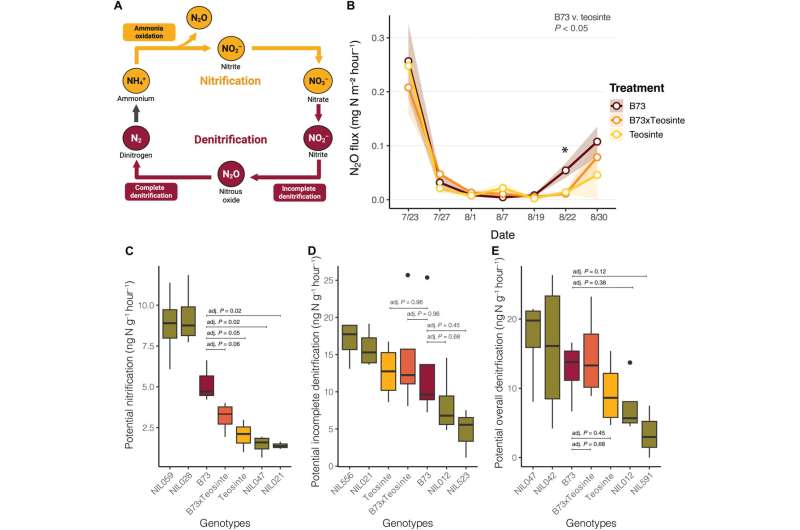

In a study published in Science Advances, researchers compared modern corn with maize lines integrated with specific, inherited traits from teosinte. They found that these traits create distinct microbial environments in the rhizosphere—the narrow zone of soil around their roots—subtly affecting nitrogen cycling under field conditions.

"The key here is we can use wild genetic variation in our crops to make our modern agricultural system more sustainable," said Alonso Favela, lead author on the study and a plant microbial ecologist at the University of Arizona School of Plant Sciences.

It's an increasingly popular way of thinking about sustainability in agriculture, focused on reconnecting modern crops with traits tied to their evolutionary history. Researchers are already looking at wild crop relatives for characteristics such as heat tolerance and pest resistance. Favela's research team focuses underground, on ancestral traits that may increase nitrogen efficiency.

Click here to see more...