By Jonathan Coppess, Gary Schnitkey.et.al

On November 15, USDA announced issuance of the second tranche of Market Facilitation Program (MFP) payments for 2019 (USDA, November 15, 2019). As of November 18, 2019, USDA reports that MFP 2019 has paid $6.898 billion of the announced $14.5 billion; MFP 2018 is reported to have paid farmers $8.59 billion. MFP makes direct cash payments to farmers of select commodities and was created by the Trump Administration, not Congress. The program’s stated goal is to help farmers who have been impacted by the tariff conflict the Administration initiated in 2018. This article continues evaluation of this program with perspectives on its place in the larger agricultural policy debate.

Background

The first shots of the tariff conflict were launched by the Trump Administration beginning with solar panel and washing machine tariffs on January 1, 2018 followed by the announcement on March 1, 2018, of aluminum and steel tariffs. By April of that year, the Administration had levied $50 billion on Chinese goods and China had begun retaliation; the conflict escalated from there reaching $200 billion in tariffs on Chinese goods by July and crop prices, especially for soybeans, fell precipitously (farmdoc daily,

July 31, 2018). In August 2018, the Trump Administration initiated the Market Facilitation Program (MFP) using longstanding general authorities under the Commodity Credit Corporation Charter Act of 1948 to distribute billions in direct payments to farmers of certain commodities that had been impacted by the tariff conflict as key crop prices continued to fall (farmdoc daily,

August 28, 2018; October 11, 2018). Notably, these efforts by the Administration coincided with Congressional efforts to reauthorize the farm bill, including the commodity assistance programs that provide billions in direct payments to farmers of a select group of bulk commodities, some of which were covered by MFP 2018 (farmdoc daily,

August 9, 2018). It took the mid-term elections and the pending change of power in the House of Representatives to break the farm bill stalemate; Congress enacted the Agricultural Improvement Act of 2018 in December (farmdoc daily, December 12, 2018). On

December 17, 2018, USDA announced a second round of MFP payments bringing the estimated total spending to $9.567 billion, including assistance to almonds, hogs and sweet cherries not covered by the farm bill programs (USDA Press Release,

December 17, 2018). In spring of 2019, the tariff conflict continued and farm bill implementation was underway; on May 23, 2019, the Trump Administration announced MFP 2019 promising $14.5 billion in additional payments, covering an expanded list of commodities (USDA Farmers.gov,

Market Facilitation Program). The timing was particularly notable as the announcement hit during the middle of an incredibly wet spring as many farmers struggled with a difficult planting season.

Discussion

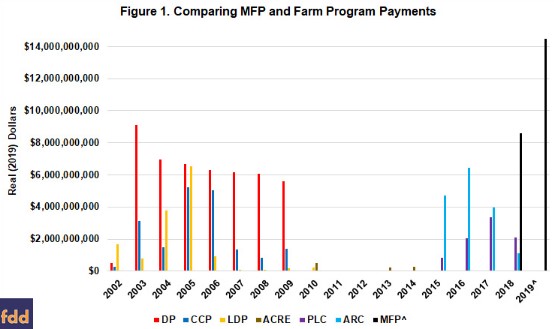

The first thing that stands out about MFP is the sheer size of the spending under the program. If all three tranches of MFP 2019 are made—and there is little reason to doubt that they will—the total spending for both the 2018 and 2019 versions could exceed $24 billion. Figure 1 places MFP among the direct payment programs of the most recent farm bills, with payments reported by the Economic Research Service (ERS,

Government Payments by Program). Figure 1 covers the farm programs in the 2002, 2008 and 2014 farm bills: direct payments (DP); counter-cyclical payments (CCP); loan deficiency payments (LDP); average crop revenue election (ACRE); price loss coverage (PLC); and agriculture risk coverage (ARC). The payment amounts have been adjusted for inflation by ERS to real (2019) dollars. MFP 2018 and 2019 are included at the level of payments reported or announced (promised) by USDA; payments for the 2018 Farm Bill commodity programs are not included because the first year of payments (2019) will not be made until October 2020.

MFP assistance is different in critical ways from the other programs. It was not authorized by Congress in either the 2018 Farm Bill nor in any ad hoc appropriations legislation. The payments were made available to farmers using existing authorities of the Commodity Credit Corporation (CCC). The final rule specifies that payments are made pursuant to Section 5 of the CCC Charter Act of 1948. The relevant parts of Section 5 authorizes assistance to “aid in the removal or disposition of surplus agricultural commodities . . . [i]ncrease the domestic consumption of agricultural commodities (other than tobacco) by expanding or aiding in the expansion of domestic markets or by developing and aiding in the development of new and additional markets, marketing facilities, or uses for such commodities” (USDA,

CCC Charter Act). USDA explained that the MFP payments were permissible under Section 5 because they “will provide producers with financial assistance that gives them the ability to absorb some of the additional costs from having to delay or reorient marketing of the new crop due to the trade actions of foreign governments resulting in the loss of exports” (USDA,

Trade Mitigation Final Rule, at 3). From a legal perspective, this is arguably a very creative interpretation of the CCC Section 5 authorities.

In many ways, the interpretation of CCC authorities becomes a confusing tangle of technicalities that obscures a larger point. The larger point is simply this: under the Constitution, it is Congress that has been vested with the legislative power as well as the power of the purse; the Executive Branch, and its agencies such as USDA, has only that power which Congress has delegated to it via duly enacted statutes. There is a long-running legal and academic debate about the power and authority of agencies to interpret and reinterpret statutes, including how far they can stretch the delegation through creative interpretations (see e.g., farmdoc daily,

August 22, 2019). To be clear, the implications of this for MFP likely remains largely academic; someone would have to initiate litigation against USDA to contest its use of CCC authority and, more importantly, it is likely that Congress will have been found to have accepted USDA’s interpretation based on the fact that it has replenished the CCC borrowing authority without addressing USDA’s interpretation. This reality, however, serves to substantially magnify the precedential weight of MFP and its impact on farm policy going forward. For those reasons, among others, it should reasonable to expect full transparency from the Administration regarding the justifications and design of MFP.

When Congress creates farm policy and designs programs to make direct assistance to farmers it does so in an open and deliberative process designed by the Founders in Article I of the Constitution. Committees produce bills that are reviewed by others on the committee, analyzed by USDA, the Congressional Budget Office and academics. These bills are reported on and subjected to public scrutiny. More importantly, members of the committee have the ability to debate, amend and vote on the bills; to become law, any Congressionally-designed farm assistance program must survive an arduous legislative process and receive the support of at least a majority of the 435 duly elected members of Congress. In contrast, MFP was created because President Trump directed the Secretary of Agriculture to provide assistance to farmers due to the tariff conflict and, specifically, the retaliatory tariffs from key agricultural export markets such as China. USDA developed the specific aspects of MFP in a truncated rulemaking process. While USDA has provided documentation as to the methodologies used to calculate MFP payments in 2018 and 2019 (USDA, 2018; USDA, 2019), both were published after the rulemaking process was completed. In total, the MFP process has left substantial unanswered questions.

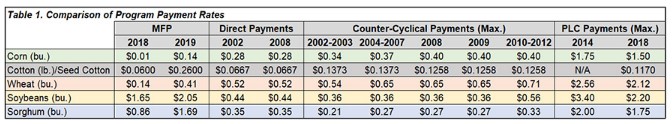

To provide further perspective on this matter, Table 1 compares the program payment rates for the major farm programs of the 2002, 2008, 2014 and 2018 farm bills with MFP’s payment or commodity rates as announced by USDA. The maximum counter-cyclical payments (CCP) and PLC payments have been calculated based on the statutory provisions of the relevant farm bills. For CCP, the statutory target price is reduced by the direct payment rate, and then the marketing assistance loan rate is subtracted to reach the maximum per-unit rate. For PLC payments, the loan rate is subtracted from the statutory reference price to get the maximum per-unit rate. Because cotton was removed from the programs in the 2014 farm bill a maximum rate from 2014 is not available; cotton was restored in 2018 as seed cotton with a reference price of $0.3670 per pound and a loan rate of $0.25 per pound for a maximum rate of $0.117 per pound (see e.g., farmdoc daily

, January 11, 2018;

February 14, 2018).

If it does anything, Table 1 in combination with the spending illustrated in Figure 1 raises many questions about the MFP program and, in particular, the 2019 version’s commodity rates; questions that have thus far not been adequately addressed by the Administration.

There are other issues with MFP not addressed. For one, Congress decoupled farm program payments from the planting and production decisions at the farm level in 1996. This substantial reform of farm policy was 63 years in the making; the product of numerous debates, disputes, evolutions and mistakes from which much was learned. MFP has fully recoupled payments to production decisions. The 2018 version was based on actual production records of the crops for which payments were made, although the program was announced after planting decisions had been made. The 2019 version required that the farmer plant a crop to receive any payment, including eventually accepting the planting of a cover crop on prevent planting acres in return for the minimum $15 per acre payment. The rollout of the 2019 version and the timing of its announcement were further complicated by the difficult spring planting season in the Midwest. With MFP, the Administration has created a payment program that represents a major redirection of farm policy away from the decoupling efforts by Congress over the past 22 years (1996). It has done so, more importantly, without any public debate or evaluation of the market impacts; neither have the implications under our World Trade Organization (WTO) commitments received full and public analysis. MFP may well constitute a real inflection point in farm policy but one without public deliberation by elected representatives and with only a modicum of explanation or justification.

The 2019 version also made payments using a single county wide payment rate (based on the commodity rates and production histories of the counties) that differs by county and region with the largest payments noticeably concentrated in southern counties that have cotton production histories. Moreover, the MFP program created its own payment limitations that were set at levels more than double the payment limit levels established by Congress for ARC/PLC payments. This incredibly contentious issue has been debated and hotly contested in farm bill reauthorization debates for the entire history of farm policy. Questions about these matters and more remain unanswered to date.

Concluding Thoughts

At this moment, mired in the fog of uncertain, tumultuous times, we do not know exactly what the Market Facilitation Program signals for farm policy going forward. We do know that it is unprecedented in terms of the size of the total payments, the way in which they were created, the significant change in policy, and the use of Commodity Credit Corporation authorities created by Congress in 1948 in the wake of the Great Depression, the Dust Bowl and World War II. History teaches quite clearly that policy movements of this magnitude establish precedents going forward; the level of expenditures will most certainly impact the future of farm policy. Despite some of the claims of the President, MFP payments are made from taxpayer funds through the borrowing authority of the Commodity Credit Corporation which has to be replenished by Congressional appropriators; they are not offset by tariffs levied on American consumers of imported Chinese goods. At the very least, this massive investment in farmers of taxpayer funds raises serious and important matters that all call for far greater transparency, justification and explanation by the Administration, as well as more scrutiny by Congress and the public.

Source : farmdocdaily