By Anna Wallis and Emily Lavely

Series of photos illustrating click pruning cuts. Photo by Todd Einhorn, MSU.

What is click pruning?

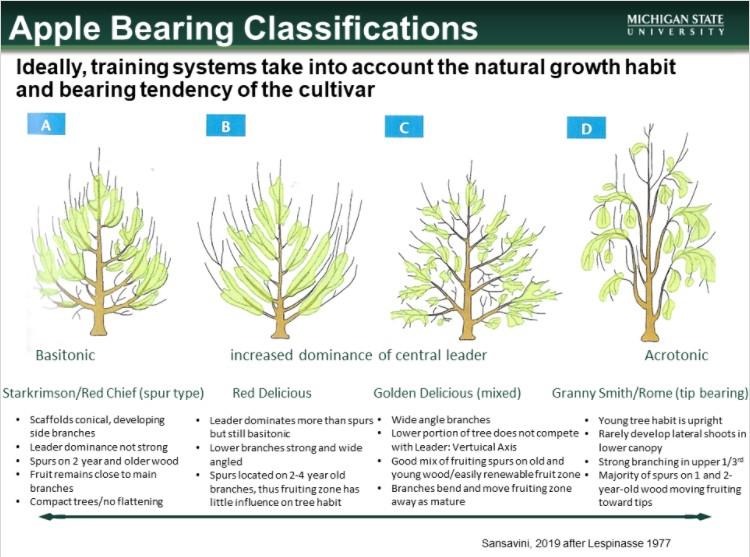

Click pruning is a technique that was developed in the past two decades in Northern Europe. It has been further developed and promoted by Stefano Musacchi for type-4 and tip-bearing cultivars (acrotonic, or “D” in the figure below) that often present blind wood. Musacchi is the research pomologist with Washington State University (WSU) Tree Fruit Research and Extension Center in Wenatchee, Washington.

Musacchi also refers to click pruning as “tira savia.” In Spanish, this means “to pull the sap.” By pulling the sap flow to the end of the branch, you are driving vigor in a specific zone of the branch.

The main goals of click pruning are to control vigor and reduce blind wood. This helps promote spur development closer to the center of the tree. It is used often in high density pears, which are extremely vigorous and prone to blind wood. It is also very useful for some apple varieties, especially vigorous, tip-bearing varieties such as Fuji and Evercrisp.

Apple bearing classifications. Photo by Todd Einhorn, MSU.

Apple bearing classifications. Photo by Todd Einhorn, MSU.When to use the click pruning technique

Click pruning is best for tip-bearing, type-4 cultivars and to reduce blind wood, directing fruit production closer to the center of the tree. Todd Einhorn, a professor in tree fruit physiology with Michigan State University Extension, summarized the best opportunities for using click pruning:

- On young (1- and 2-year-old) trees when tight spacing, high vigor or renewal branching is needed.

- When setting the terminal height of a tree that has limited subtending, weak wood.

- On cultivars that have a class 4 growth habit, tip bear and produce upright and vigorous wood.

- Where blind wood is an issue.

- On very weak wood where vigor is needed. This could be the weak axis of a multi-leader, a weak axis of a spindle or a weak lateral branch.

- At the base of multileader systems where vigor tends to be limiting.

How to click prune

Click pruning involves several steps. The main idea is to tip branches using a heading cut into 1-year-old wood. This causes the buds directly below to break and develop several new shoots. This drives sap flow to the shoot and feeds the branch below to promote fruit bud or spur development.

- In year one, starting with feathered trees, begin with dormant pruning. Cut feathers back to a stub, as in a renewal cut.

- Over the growing season, you will see several buds break and shoots develop.

- In the next year, during dormant pruning, select the renewal shoot. Choose a horizontal limb, not too vigorous, and remove the others. Then, head or tip this shoot.

- Over the next growing season, several buds will break and grow vegetatively. These shoots will fuel growth and induce floral bud or spur formation below to produce a crop in the following season.

- Continue to use this technique in a three-year cycle, renewing branches. Renew in year one, tip in year two, and bear fruit in year three. Keep branches on the tree that are in each stage in order promote a crop in each year.

Source : msu.edu