Seed dormancy is an important survival tool for plants because it allows them to weather conditions not conducive to survival. At the same time, excessive dormancy may lessen cultivation time. In response, farmers often plant low dormancy cultivars of rice and wheat in order to achieve a higher, more uniform emergence rate after sowing.

Unfortunately, this practice has led to an unwanted worldwide production problem called pre-harvest sprouting (PHS), which severely reduces both grain yield and quality. In rice, PHS damages about 6% of the acreage of conventional rice and as much as 20% of hybrid rice acreage due to the long-term rainy weather during the harvest season in southern China. In bread wheat, the direct economic loss caused by PHS approaches $1 billion per year.

With global climate change, PHS has been occurring more frequently. For example, the major wheat production areas, especially the winter wheat regions of the Middle and Lower Yangtze River Valley and the Yellow and Huai Valleys in China, encountered serious PHS problems in 2013, 2015, and 2016. Heavy rainfall in 2016 and 2020 also led to serious PHS problems in the rice planting regions of the Middle and Lower Yangtze River Valley of China.

In an effort to solve this problem, researchers led by Profs. CHU Chengcai and GAO Caixia from the Institute of Genetics and Developmental Biology (IGDB) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) recently revealed that the SD6/ICE2 molecular module controls rice seed dormancy and has great potential for improving PHS tolerance in rice and wheat.

The study was published in Nature Genetics.

In this study, the researchers used a set of chromosome single segment substitution lines derived from a cross between the weak-dormancy japonica rice cultivar Nipponbare and the strong-dormancy aus rice cultivar Kasalath to identify a gene, named as Seed Dormancy 6 (SD6), that contributes to rice seed dormancy.

The researchers found that SD6 and its interaction partner ICE2 antagonistically control rice seed dormancy by regulating abscisic acid (ABA) homeostasis. Specifically, SD6 directly promotes the expression of the ABA catabolism gene ABA8OX3 and indirectly inhibits the expression of the ABA biosynthetic gene NCED2, while ICE2 acts in an opposite manner.

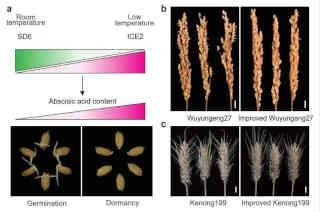

Temperature has a major effect on the strength of seed dormancy. The researchers revealed that the SD6/ICE2 molecular module controls rice seed dormancy in a temperature-dependent manner: SD6 is up-regulated to trigger seed germination when seeds are at room temperature. However, at low temperature, SD6 is down-regulated while ICE2 is up-regulated to maintain seed dormancy.

By editing SD6 in three rice cultivars, T619, Wu27, and Huai5, the researchers found that gene editing of SD6 could be a rapid and useful strategy for improving PHS tolerance in rice. Interestingly, editing the TaSD6 gene in the wheat variety Kenong199 also greatly improved PHS resistance in wheat, indicating that the SD6 gene is functionally conserved in controlling seed dormancy in both rice and wheat.

In summary, SD6 and ICE2 regulate seed dormancy by fine-tuning ABA content in seeds depending on temperature. In this way, they help seeds overcome natural seasonal change and ensure successful reproduction. For this reason, SD6 may be a powerful target for improving PHS resistance in cereals under field conditions.

Click here to see more...