By Jonathan Coppess

Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics

University of Illinois

The USDA farm loan programs originated in 1937 as part of the late New Deal efforts to address problems of the Great Depression (farmdoc daily,

March 4, 2021). Congress enacted substantial revisions to the lending programs, including creation of insurance for farm mortgages, after World War II with the 1946 Act (farmdoc daily,

March 11, 2021). This article completes review of the early history and development for these programs, from the 1937 Act to the Consolidated Farmers Home Administration Act of 1961.

Background

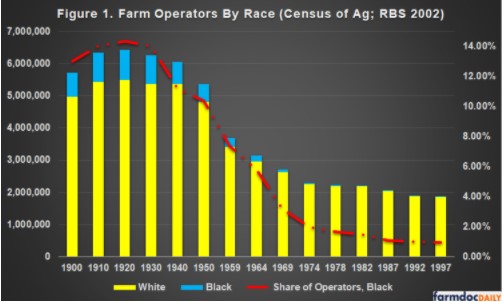

Data issues continue to challenge analysis; insufficient data is available and records from the early decades may not be entirely accurate or reliable. There remain significant questions about the data that is available, moreover, including a strong likelihood that Black farmers were undercounted or underreported (1982 USCCR; Mitchell 2005). What evidence there is, however, provides striking indications of the substantial damage over time. One comprehensive review of research reported that 14 percent (926,000) of all U.S. farmers were Black in 1920 and that Black farmers owned more than 16 million acres (Gilbert, Sharp and Felin 2002). In 1997, the Census of Agriculture reported only 20,000 Black farmers and only 2 million acres owned. A previous USDA report provided an overview of the collapse in Black farm operators since 1900. Figure 1 illustrates the data for farm operators as reported by USDA, including the numbers of white and Black farmers as well as the percentage of total farm operators reported as Black (Reynolds,

USDA-RBS 2002).

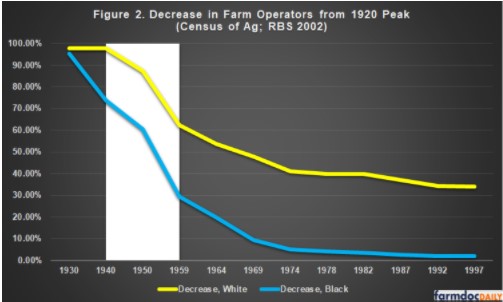

The Census of Agriculture data of farm operators indicates a peak in 1920 with nearly 6.5 million farm operators, of whom 925,708 (14%) were Black and nearly 5.5 million (85%) were white; almost 30,000 were listed as other. That peak held through the 1930 Census of Ag but began to fall under the Great Depression and the New Deal. The number of all farmers decreased in the years after World War II, but the decrease in Black farmers was both greater and faster. By 1959, Black farm operators had fallen to below 30 percent of the 1920 peak while white farm operators were above 62 percent of the peak. By 1969, USDA reported 87,393 Black farm operators, just 9 percent of the 1920 peak while white farm operators had fallen to 48 percent of the 1920 peak. One estimate concluded that if Black farmers had left farming at the same rate as white farmers, there would have been approximately 300,000 Black farmers as recent as the 1997 Census instead of 18,451 (Daniel 2013). Figure 2 illustrates the decrease in Black and white farmers from the USDA summary data calculated as a percentage of the 1920 peak.

For the history and development of the USDA lending programs, even this incomplete and challenged data provides important perspectives. The twenty years 1940 to 1959 appear to have been the most significant and those years are highlighted in Figure 2. After World War II, American agriculture underwent a technological revolution and the number of all farmers declined. These years also encompass the origin and critical early developments of USDA lending policies.

Discussion

As discussed previously, the 1946 Act revised the tenant mortgage program created in 1937. Among the revisions, were relatively subtle shifts such as loans to “refinance indebtedness against undersized or underimproved units” for “owners of inadequate or under-improved farm units” (P.L. 79-731). Less subtly, Congress also terminated all resettlement and rehabilitation efforts in the 1946 Act, programs that had been arguably the most helpful to Black farm families, cooperative projects and communities (Baldwin 1968). In 1961, the Senate Agriculture and Forestry Committee’s report on the bill claimed it was undertaking the first major revision to the lending programs since the 1946 Act (S. Rept. 87-566). Congress had made a few significant changes in 1956, however. Most notably, Congress added “farm owners” to the list of eligible borrowers for farm purchase loans and mortgage insurance, at least those considered “bona fide farmers who have historically resided on farms and depended on farm income for their livelihood” but (P.L. 84-878). This was part of a trend in the policy.

Congress rewrote the farm loan program authorities in the Agricultural Act of 1961, Title III of which was the Consolidated Farmers Home Administration Act of 1961 (P.L. 87-128). The Senate Agriculture and Forestry Committee explained that, since 1946, “the revolution occasioned by the mechanization of farming operations generally, the change in character and extent of resources necessary to successful operation of family farms, and the increase in farming technology have made tremendous differences in the credit needs of farmers” (S. Rept. 87-566, at 64). In the most significant policy change, the loans were no longer specifically for farm tenants, laborers or sharecroppers. All farmers and ranchers who were U.S. citizens and “are or will become owner-operators of not larger than family farms” were eligible for ownership and operating loans if they proved they possessed “a farm background and either training or farming experience” that was considered sufficient “to assure reasonable prospects of success” but were “unable to obtain sufficient credit elsewhere” on reasonable terms (P.L. 87-128). Congress continued the preference for borrowers who were married or had dependent families, as well as those able to make the initial down payment or owned livestock and “farm implements necessary successfully to carry on farming operations” (P.L. 87-128). Operating loans were available for inputs and supplies, but Congress also authorized loans for “costs incident to reorganizing the farming system for more profitable operation” and refinancing outstanding debt, as well as for “financing land and water development, use, and conservation” efforts (P.L. 87-128).

Most critically, the 1961 Act continued the primary role of county committees, providing them with vast discretion and ability to impact the loan making decision. A county committee of three members was to be appointed by the Secretary, two of whom had to be farmers in the county. Loan applicants had to certify in writing to this county committee that they were unable to obtain credit on reasonable terms from other lenders. The county committee continued to certify whether the loan applicant met the eligibility requirements and had the “character, industry, and ability to carry out the proposed farming operations and will, in the opinion of the committee, honestly endeavor to carry out his undertakings and obligations” (P.L. 87-128). In addition, adjustments or reductions could not be “upon terms more favorable than recommended by the appropriate county committee” and outstanding debt of more than five years could be released or charged off but only “upon a report and favorable recommendation of the county committee” (P.L. 87-128).

Consider these changes in reality; a committee made up of farmers from the county would have nearly unchecked judgment as to whether an applicant possessed the proper farming background, training or experience to succeed and whether that applicant was unable to obtain reasonable credit elsewhere. These same appointed farmers would also have to certify to the applicant’s character and ability to farm. The discretion provided the county committee would have magnified the revisions to eligibility, which had been shifted to all family-sized farmers and ranchers rather than just tenants, laborers and sharecroppers. Even without the prior history of the USDA lending programs, this arrangement in the South would be a real problem for the few remaining Black farmers. After nearly a quarter of a century’s experience with this system, there could have been no confusion about how continuing this arrangement would operate in that region, particularly with the change in emphasis away from the poorest and lowest level of farmers (USCCR 1965; Browne 1973). The results speak for themselves.

From 1937 to 1947, an earlier study found that USDA made $293,876,733 in tenant purchase loans to 47,104 families (Banfield 1949). Adjusted for inflation, this would be the equivalent of more than $3 billion in 2021 dollars. By 1963, USDA’s Farmers Home Administration managed 230,000 borrowers with outstanding debt exceeding $2 billion (USCCR 1965). Adjusted for inflation that debt would be the equivalent of $17 billion in 2021 dollars. While many Black farmers received loans from USDA, the loans were smaller and more often for purposes other than to purchase farmland. Black borrowers also received less technical assistance and supervision. Overall, they received “less in the way of benefits than [] white farmers of comparable economic assistance” in spite of the “fact that FHA’s central function is to raise the economic level and increase the opportunities of low-income farm families” (USCCR 1965, at 81). Thirty-two years after the lending programs were created to help farm tenants, laborers and sharecroppers purchase farms, the total number of Black farm operators had fallen below 10 percent of the total number in 1920. By comparison, the number of white farm operators in 1969 was 49 percent of the number in 1920.

Any analysis will find it difficult to disentangle the impact of the USDA lending programs from those of the Great Depression and World War II, as well as from the troubling discrimination, segregation and violence of the Jim Crow South; individual human stories something more than horrendous (see e.g., Conrad 1965; Baldwin 1968; Daniel 1972; Daniel 2013; Wilkerson 2010; Wilkerson 2020). The programs of farm policy, including the farm purchase and operating loans, most certainly contributed and that contribution was no accident. Southern Members of Congress were products and protectors of the segregated system, they designed the lending programs to help primarily white farmers, tenants and sharecroppers. USDA officials, especially the farmers appointed to county committees, more than complied with that Congressional intent. Devolution to local decision makers, reinforced by officials elected and appointed, was a method tried and proven to be effective (USCCR 1965; USCCR 1982; Bensel 1984; Katznelson 2013). The USDA programs were an exemplar, not an exception.

Conclusion

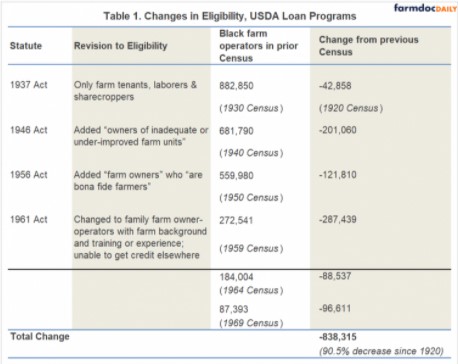

In the fog of history, too much of the truth may well be buried with the bodies. That is not the same, however, as concluding that it is unknowable or cannot be understood. The full and precise measure of the damage done may be incalculable, but that is not to say that it is impossible to estimate. Within the fog are important guideposts and markers to assist with a better understanding, which begins with an acknowledgement of the systemic nature of the problems; systemic, it persists to this day and against efforts to address it. The problems persist in large part because discrimination and disparate treatment were designed into the programs, and hard-wired into the policies, from the start. Those outcomes were subsequently reinforced time and again, including through appropriations, hearings and legislative revisions. As highlighted in Table 1, Congressional revisions to the policy continued and compounded the disparate treatment by pushing the loans further away from those farmers most in need which were, not coincidentally, Black farmers in the South.

To conclude this review of the early history and development of USDA lending programs (1937 to 1961) is to wrestle with the paradox in policies that help many but also hurt many, which begs questions about the damage done. Searching through the fog of history is to glimpse some guideposts on the periphery, including from farm policy. Better calculations and estimates remain burdened by challenges with data and history (Mitchell 2005), but even incomplete data can be informative. One estimate of 800,000 acres lost by Black farmers in Mississippi from 1950 to 1964 translated that land loss into between $3.7 billion and $6.6 billion of financial loss (Newkirk,

September 2019). Another estimate puts the total lost wealth closer to $300 billion (Philpott,

November 19, 2020). For context on these and other estimates, note that USDA ERS reported total value of farm real estate of approximately $2.6 trillion (USDA ERS

Assets, Debt, and Wealth). Black farmers may have lost 14 million acres of farmland since 1920 and this does not account for acreage that Black farmers were prevented from purchasing, including through USDA lending programs. Consider further that 14 million acres estimated to have been lost would exceed the average acres planted to cotton from 1996 to 2020 (12.8 million acres). Reviewing reported CCC outlays for upland cotton since 1961 (not adjusted for inflation) finds at least $95 billion in federal payments (see, USDA,

OBPA and

CCC; CBO; farmdoc daily,

April 5, 2018;

May 3, 2018). Since 1949, the eleven states of the former Confederacy have received total direct government payments exceeding $269 billion, adjusted for inflation and reported by USDA’s Economic Research Service (USDA ERS,

Farm Income and Wealth Statistics).

And yet, no set of numbers can properly account for the human losses. Such losses span the personal and the fundamental, philosophic importance of land ownership and farming to self-government and a democratic society. Often called agrarian democracy, and too often linked to Thomas Jefferson when John Taylor may have been its primary progenitor, it posits that small landholders are critical to a functioning democracy and self-government because they present the best defense against tyranny and concentrated power (Griswold 1946; McConnell 1951; McConnell 1953). Thus, taking land from, or preventing the purchase by, small farmers because of the color of their skin is damaging to a free, self-governing society (Mitchell 2001). If all else fails, try empathy: anyone born and raised on a farm can surely grasp the immense pain and suffering that would accompany the loss of a family’s farmland based upon arbitrary or nefarious reasons. Compounded and magnified across millions of acres, persons and families taking place over decades featuring a primary role by federal policies and officials; here begins understanding.

Source : illinois.edu