By Deah Lieurance

Recently, interest has resurfaced in the possibility of growing bamboo in Florida as a biomass crop. Bamboo has been called “green gold” and “the world’s most amazing plant,” with uses ranging from structural materials to industrial products, fencing and even food. However, there are many uncertainties surrounding growing bamboo for commercial purposes. These uncertainties include risk of the bamboo becoming yet another invasive species, challenges in production and availability of consumer markets.

“Dendrocalamus asper (Serres de la Madone) leaf” by Tangopaso – Self-photographed. Licensed under Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Invasion risk

There are two major types of bamboo: clump forming and running. Generally, running bamboos thrive in temperate climates and are a high risk for invasion; the less risky – but not risk-free – clumping bamboos prefer tropical or subtropical conditions. Still, both require management to keep them contained.

As an Extension scientist and coordinator of the UF/IFAS Assessment of Non-Native Plants in Florida’s Natural Areas, I must caution farmers interested in growing bamboo that many bamboo species pose an invasion risk for the state.

The UF/IFAS Assessment provides conclusions about many species of bamboo. The two prominent species in production in the Southeast are the clump forming Dendrocalamus asper (often called Asper or Tropical Asper) and the running Phyllostachys edulis (Giant Moso Bamboo, Moso, or Edulis bamboo). Dendrocalamus asper is labeled as a moderate risk to Florida, meaning strict management is required to prevent escape, and all Phyllostachys species are a high risk for invasion, including Moso. In fact, Phyllostachys aurea (Golden bamboo) is currently invading the Southeast from Texas to Florida, up to Kentucky and Virginia!

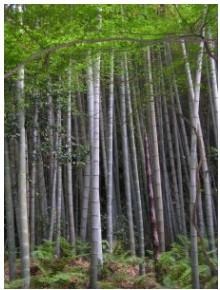

“Bamboo forest”. Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Permitting

Additionally, farmers should be informed that in Florida, any biomass planting of 2 acres or more requires a permit from the Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services Division of Plant Industry (FDACS DPI). A UF/IFAS Extension document I co-authored, “Navigating the Non-Native Planting Rule: Permit Requirements for Large-Scale Plantings of Non-Native Species in Florida,” explains the process in detail.

Production challenges

Another concern that should be mentioned is challenges in production itself. Growing on a commercial scale involves site preparation, fertilization and harvesting in dense bamboo stands, and stands must be strictly managed to prevent spread outside cultivation. Climatic tolerances differ in the types of bamboo, so you must be certain you are growing the right bamboo for your area. The challenges don’t end at harvest, either, as viable markets to sell bamboo products may not readily exist.

For more on growing bamboo in the Southeast, check out this regional extension document, “Growing Bamboo for Commercial Purposes in the Southeastern US: FAQs,” co-authored by experts from Clemson University, Auburn University, the University of Georgia and UF/IFAS. This document provides broad guidance on the prospect of planting bamboo for biomass, carbon sequestration, and/or food.

In short, before deciding to grow bamboo, farmers should be aware of the risks and work with their local Extension agent to see if the crop is right for them. In Florida, please reach out to your local UF/IFAS Extension agent with any questions regarding bamboo.

Source : ufl.edu