By Ed Barnes

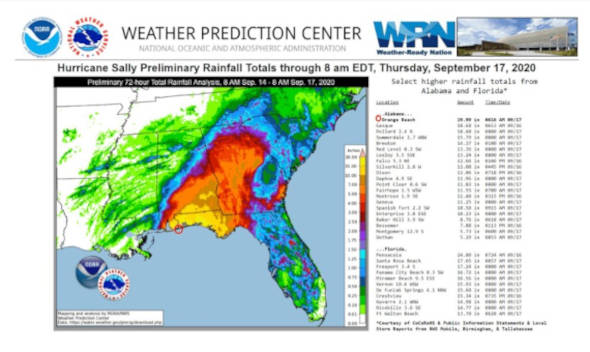

Seed coat fragments (SCFs) have been a long-term issue for cotton. Outbreaks of SCFs occur sporadically every 3 to 5 years in a region of the U.S. In 2020 the region included Alabama, Georgia and Florida with the biggest outbreak of SCFs calls in the last 20 years. And it is no coincidence that this was also one of the worst years for tropical storms in this region. SCFs are formed when a part of the cottonseed wall is broken off, and that broken wall is often attached to some fibers, making it particularly difficult for the gin and textile mills to remove, as all their equipment is designed to keep fibers in the process.

SCFs have been studied for a long time, and Cotton Incorporated has sponsored a consistent research program on SCFs reduction since 2003 with the USDA-ARS gin labs, Texas Tech University, and NC State University. We have learned a lot over that period of time and before sharing – I want to emphasize, there is strong evidence that what we are seeing in this year is highly weather related. When open bolls get wet, three things can happen that will lead to seed coat fragments:

- seed sprout – if the seed sprouts in the boll, there will definitely be seed coats in the cotton when that cotton is ginned;

- wet seed at the gin – cotton lint dries much faster than the seed. This can lead to cotton being harvested when it appears dry but the seed is still wet. Wet seed will be pulled through the ribs of the gin stand and forms seed coats;

- wetting and drying of seed in the field – when the seed takes up moisture in times of high humidity it will expand and then shrink as it dries. A few cycles of wetting and drying and the seed coat becomes weak and can easily break during the harvest and ginning process. All three of these likely contributed to SCFs this year.

I have heard a few theories about what caused SCF problems this year beyond weather, and I can dismiss a few. One theory to dismiss is that the Macon classing office made too many SCF calls. The USDA-AMS classing system has a very robust set of checks and balances. They were aware early in the season an anomaly was occurring and were careful to make sure they were properly defining seed coat fragments. As some evidence, I can personally confirm that Cotton Incorporated’s Fiber Processing lab purchased four bales from Georgia that had SCF calls and they were indeed full of SCFs. On the plus side, those bales were purchased so our textile experts can process them and provide assistance to mills on how to handle this year’s SCFs. SCFs can be a real challenge for mills if not handled correctly – in addition to potentially ending up in a fabric, in a worst-case scenario, the oil in the SCFs can coat the equipment and require the mill to shut down for cleaning.

In past years when SCFs were a problem, there was often a strong variety by environment interaction (for example, a particular variety has SCFs one year when other varieties do not, and then in another year that same variety does not have SCFs). There is not conclusive evidence variety was not a factor this year; however, the fact that there were not problems in SC and NC where some of the same varieties are grown reinforces the hypothesis that weather was the dominant factor. Finally, keep in mind the first boll on a plant opens at the bottom when it is hidden from sight and will occur anywhere from 50 to 70 days before the crop is harvested. Those bottom bolls are the ones most likely to stay wet.

Percent of bales with seed coat fragment calls by count as of Dec. 11, 2020 and approximate paths of three of the 2020 hurricanes. Map on the complements of the National Cotton Council using SCF data from USDA-AMS.

Cotton Incorporated funded research is making progress in addressing seed coat fragments by improving the lint cleaner at the gin, and in developing tools that could help breeders screen for genotypes that are prone to seed coat fragments in the future. We have found that seed size is not a good predictor of SCFs, but how strongly the fiber is attached to the seed (attachment force) and seed coat strength are. Why is this problem still not solved? Part of it is the infrequent nature of SCFs and the interaction between variety and environment. We will continue to work on SCFs with the hopes the next time they occur we can further reduce the problems they cause and hopefully reduce the frequency of such events.

Source : ufl.edu