By Mike Staton

Many soybean fields across Michigan experienced uneven and significantly delayed emergence due to the dry weather and soil conditions that prevailed after mid-May (Photo 1). Seed placed into 0.5 inches of soil moisture germinated and emerged well while seed placed into marginally moist or dry soil did not germinate and emerge until the rains resumed in July. In the most extreme cases, emergence was delayed by five weeks or more within a given field.

The delayed and uneven emergence will lead to significant in-field variation in maturity this fall, and producers will have to identify the harvest timing that maximizes net income in these fields. In general, soybean maturity is delayed by one day for every three days that planting/emergence is delayed. Given this information, a 30-day difference in emergence will cause at least a 10-day spread for optimum harvest dates. While 10 days may not sound like a big deal, producers need to understand how factors such as shatter losses, lost yield from overly dry seed, drying charges and discounts, and potential storage problems will affect net income when selecting the optimum harvest timing.

Uneven ripening is common in soybean fields, however the situation in 2023 is different. In most years, the areas that dry down first have lower yield potential than the rest of the field. In 2023, the areas that will dry down first have more yield potential because they emerged earlier and had a longer growing season.

Producers have four options for harvesting unevenly maturing fields:

- Harvest each affected field at two different dates.

- Harvest the entire field as soon as the early emerging plants are ready.

- Delay harvest until the late emerging plants are ready to harvest.

- Compromise and harvest the field when the late emerging plants first reach 16% moisture.

Harvesting affected fields on two different dates corresponding to the optimum times for the early and late emerging plants will minimize all the potential problems stated above. However, this is not practical, and few producers will consider this option.

Harvesting the entire field as soon as the earlier emerging plants are ready will reduce shatter losses and harvest delays and provide optimal harvest conditions for the plants having the highest yield potential. However, the later emerging plants may be difficult to cut and thresh and may lead to higher drying charges or discounts at delivery. Unthreshed green pods and green/immature soybeans can also create on-farm drying and storage problems. Combine operators will need to pay close attention to cylinder/rotor speed and clearance settings as they move from ripe to tough plants.

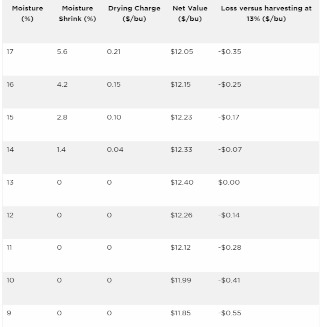

Delaying harvest until the seed in the later emerging plants reaches 13% moisture eliminates the problems associated with the early harvest option. However, if hot and dry conditions occur prior to and during harvest, shatter losses can be excessive in the early emerging plants (Photo 2). The risk of harvesting overly dry beans also increases, reducing the yield of the highest yielding areas of the field due to lost water weight (Table 1). We experienced both conditions in the fall of 2021.

This option also increases the risk of harvest delays and increased shattering due to the pods being exposed to repeated wetting and drying cycles. University of Wisconsin researchers found that harvest losses increase significantly when harvest is delayed by 14 days and continue to increase with further delays. Reducing ground speed and reel speed are important tactics for reducing shatter losses. Delaying harvest is probably a good option if the weather cooperates, and shatter losses and seed moisture losses can be minimized.

Table 1. Net value of a bushel of soybeans at various moisture levels.

Assumptions: Soybean price of $12.40/bu (2023-24 estimated average price from the July USDA WASDE report) and typical elevator shrink and drying charges for 2022.

Compromising by harvesting the affected fields a little later than the optimum time for the early emerging plants and a little earlier than the optimum time for the later emerging plants is a viable option. In theory, this option should narrow the differences between the plants from the two emergence dates. If this option is selected, begin harvesting when the seed in the later emerging plants first reaches 16% moisture.

Volunteer soybean demonstrating excessive shatter losses common in 2021. Photo by Alex Rutkowske.

If you plan to dry and store soybeans with mixed moisture levels, please consider the following information provided by Ken Hellevang from North Dakota State University.

- Unthreshed pods can block the flow in dryers and increase the potential for fires to occur.

- Immature soybeans can cause moisture meters to underestimate moisture levels by 1 to 1.5%.

- The green color may fade after several months of storage.

- Bean pods and higher moisture beans accumulate in pockets and cause storage problems.

- Run aeration fans to create a more uniform moisture content as the air picks up moisture from the wet beans and deposits it on the drier beans.

- Soybeans of mixed maturity and varying moisture content should not be stored into the summer and should be kept cool by periodic aeration.

Harvesting fields with variable maturity will be challenging this fall. However, producers can minimize harvest and storage losses through careful management.

Source : msu.edu