By Mathew M. Haan

Introduction to Rumination

Cattle, sheep, deer, and similar animals are classified as ruminant animals. As a group, ruminants share the characteristics that they are hooved mammals, with an even number of toes, that regurgitate and re-chew their feed. This cud chewing or rumination process is the characteristic that gives the group its name. The rumination process allows these animals to eat forages and other high fiber feeds that are not be able to be eaten by humans and other non-ruminant animals.

Ruminants have a four-chambered stomach, consisting of the reticulum, rumen, omasum and abomasum. Ruminants typically eat quickly with minimal chewing. After being swallowed, feed enters the reticulum, which is continuous with the rumen. The rumen is the largest of the four stomach chambers and serves as a large mixing vat that is the site of microbial fermentation and nutrient absorption. Combined, the rumen and reticulum of an adult dairy cow can hold around 50 gallons of partially digested feed.

During rumination, the cud (partially digested feed) is regurgitated, re-chewed, and re-swallowed. Chewing during rumination is slower and more consistent than during eating. The rumination process stimulates saliva production to help buffer the rumen pH and decrease feed particle size, allowing it to pass from the reticulum into the omasum. As partially digested feed passes through the omasum, water is absorbed, reducing the volume of material that arrives in the abomasum. The abomasum, often referred to as the true stomach, produces acid and digestive enzymes similar to the stomach of non-ruminant animals, further breaking down the feed before It passes into the lower gastrointestinal tract for further digestion, absorption and ultimately elimination.

The amount of time an animal spends ruminating is affected by species, breed, physical and chemical characteristics of the diet, health condition, feed intake, and production level. Approximately a third of the variation in rumination time in dairy cattle has been shown to be related to feed intake, primarily two main diet components which are NDF and starch.

Rumination can occur anytime throughout the day but tends to follow a daily pattern, with cattle spending a greater proportion of time ruminating at night and following feeding periods. Rumination is more likely to occur when cows are lying down, making it important to ensure that dairy cows have adequate, comfortable space. A dairy cow in a conventional United States dairy will on average spend between 7 to 8 hours ruminating per day. Rumination time is broken up into several individual bouts throughout the day with each bout lasting from a few minutes to over an hour. An individual bolus or cud will be chewed for 30 to 70 seconds before being swallowed.

Monitoring Rumination

Dairy producers, animal nutritionists and veterinarians have long recognized the importance of rumination as an indicator of dairy cattle health and performance. Traditionally, visual observation of rumination activity was the only on-farm option available to assess rumen health. For example, 60% or more of the herd observed ruminating at any time is considered an indicator of healthy rumen function across the herd. However, this method can be time consuming and only allows an assessment at a population level, while individual animal rumination data help producers to promptly identify specific animals that may need attention. Furthermore, this method is subject to discrepancies between observers and the time of the day that observers perform the assessment. Rumination is affected by daily practices on the farm, such as feeding, and the time during the day (e.g., day vs night). For these reasons, although visual observations of cattle to assess rumination activity could be a good estimation of cow comfort and health at a population level, this method may not provide an accurate representation of individual cow rumination.

Currently, several companies produce commercially available rumination monitoring systems. These rumination sensors are usually integrated into activity monitor devices, eartags or neck collars that are used to aid in the reproductive management on the dairy. For systems commonly used in the United States, these devices use either accelerometers to measure small changes in animal position and movement to determine rumination time or acoustic systems that record chewing behavior. Though less common, some rumination monitoring systems use a bolus placed in the rumen of the animal or a pressure sensor located on a noseband. Many of the systems available are capable of distinguishing eating behavior from rumination behavior and, in addition to rumination time, some will also report eating time.

Regardless of where the sensor is positioned on the animal or the animal housing system on the farm (freestall, tie-stall, grazing), these tags have been shown to be effective in monitoring rumination behavior. Numerous independent research studies have validated the accuracy and precision of the major systems on the market, with universities increasingly using the technology as a tool to measure rumination time in research studies.

Practical Applications of Rumination Monitoring Technology

With the increasing availability of commercial rumination monitoring systems in recent years, there has been a corresponding increase in research looking at the relationship between rumination and a wide variety of health conditions, environmental factors, nutrition and management. Much of this research is focused on using rumination as an indicator of changes in animal performance and welfare.

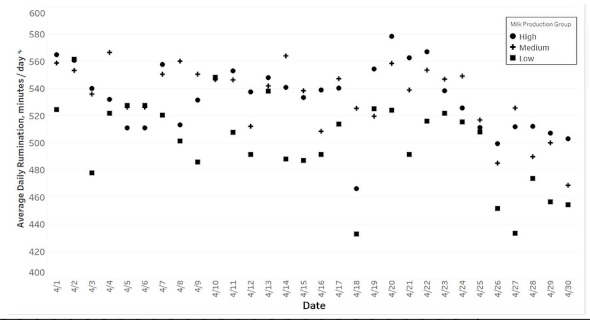

Each herd and each individual animal within a herd will have its own rumination pattern based on factors such as diet, stage of production, and other factors mentioned previously in this article (Figure 1). If cows at Farm A average 513 minutes of rumination per day while cows at Farm B average 470 minutes of rumination per day, it should not be assumed that cows at Farm A are healthier or are raised under better conditions than cows at Farm B (Figures 2A and 2B). Similarly, if Cow 2340 at Farm A averages 600 minutes of rumination per day and Cow 2450 at the same farm averages 475 minutes of rumination, it should not be assumed that Cow 2340 is in better health than Cow 2450. Comparisons in rumination activity should not be made across farms, especially when different sensors are being used on the farms. Comparisons of rumination activity between cows of the same breed and age within a herd should only be made between animals at similar stages of production. Rumination activity is most meaningful when comparing an individual animal to her own baseline rumination pattern or when comparing an individual herd to the herd’s baseline rumination pattern.

Figure 1. Average daily rumination time for mid-lactation cows (90-220 DIM on April 30 Test date). Based on April 30 milk test date, cows were divided into High (120 lbs milk, 153 DIM, 534 minutes rumination (n=19)), Medium (97 lbs milk, 162 DIM, 529 minutes rumination (n=18)), and Low (71 lbs milk, 159 DIM, 517 minutes of rumination (n=8)) production groups.

Figure 2A. Daily rumination time varies within a herd. Each point represents an individual cow average rumination time per day is 513 minutes.

Figure 2B. Daily rumination time varies within a herd. Each point represents an individual cow, average rumination time per day is 470 minutes.

Parturition and Transition Cow Health

The transition period of a dairy cow, often defined as the period from 3 weeks before until 3 weeks after calving, is a challenging time for the health and performance of the dairy cow. Metabolic and reproductive health issues associated with the transition period, including displaced abomasum, ketosis, and retained placenta, are common causes for early removal of cows from the herd. Data from the USDA has shown that approximately 20% of dairy cows will leave the herd within the first 50 days post-calving.

Several research studies have evaluated the use of data from activity and rumination monitoring systems as tools to monitor health status of cows around the transition period with the goal of early detection and prevention of transition cow health issues. These studies have consistently shown that rumination time was lower during the pre-calving period for cows that would develop a health event (stillbirths, retained placenta, displaced abomasum, ketosis, metritis) during or after calving compared with cows that would not experience health events during this time. As an example, one study showed that for cows that had displaced abomasum early after calving, the rumination time began to decrease as early as twelve days pre-calving as compared to cows that would not experience a health event post-calving.

A case study conducted on a Pennsylvania dairy (

Using Activity Systems to Monitor Dry and Transition Cows ), showed observation data that suggested that activity and rumination data during the pre-calving period could potentially be used as a tool to help farmers detecting cows that might be at a higher risk of having a health event around calving or leaving the herd prematurely. This early warning could provide farmers with an opportunity to implement best management strategies for these at-risk animals, allowing them to cope better with the transition period challenges, and therefore, decrease the risk of these animals to develop health events or leave the herd prematurely.

Even though lower average rumination time in cows pre-calving has been associated with potential health problems post-calving, almost all cows will experience a sharp decrease in rumination time immediately before calving. This sharp decrease in rumination time typically begins about 6 hours pre-calving and is associated with a decreased eating time and decreased dry matter intake. This sharp decline in rumination time could potentially be used as an indication of calving.

Heat Stress

Temperature Humidity Index (THI) combines air temperature and relative humidity to calculate an index value to better represent the environmental conditions a cow or other animal feels and is used to determine when animals are in a heat stressed environment. A THI value of 68 is generally accepted to be the threshold value for mild heat stress in dairy cattle. In an earlier paper (

Using Rumination Sensors to Monitor Heat Stress in Dairy Cows ), the author suggests that daily rumination time decreased by six minutes per day for every one THI unit increase over 60 for high producing Holstein cows housed in a tie-stall barn in southeast Pennsylvania. A German study found that rumination minutes per day for cows housed in a naturally ventilated freestall barn began to decrease when THI exceeded 52.

These studies and others indicate that cows may begin to experience heat stress well before THI reaches 68. Higher producing, later lactation and older animals may be more sensitive to high THI than other cows. Other management practices, such as type of housing, ration and availability to water, will also likely influence when cows in a particular environment begin to experience heat stress. Access to data from rumination monitoring technology on farms may help producers to identify heat stress at the population level and implement management changes before milk production or reproduction are negatively impacted.

Estrus Detection

The amount of time a cow spends ruminating each day has been shown to decrease from baseline levels around estrus. Rumination time begins to decrease the day before estrus, hitting a minimum level on the day of estrus. On the day before and day of estrus, cows can ruminate more than an hour less per day compared to baseline rumination levels. Rumination will return to baseline levels by the day after estrus. When paired with activity data, the decrease in rumination can be used to help better identify the optimum breeding time.

Conclusions

Proper rumen function is key to the health and productivity of dairy cattle, with gradual or abrupt changes in rumination being possible indication of health events. The availability of rumination monitoring technology and research focusing on its on-farm applications has grown rapidly over the past several years. At this time, changes in rumination pattern cannot be used to diagnose a specific disease but can be used as a general indicator of a change in health status or comfort that merits further investigation. No matter how good this or any other technology becomes, it is important to remember that it is only a tool to help guide the decision-making on farms and should not be seen as something that can completely replace the knowledge and skills of dairy producers, dairy nutritionists, and veterinarians.

Source : psu.edu