Farmmaps lets producers connect with others about individual farming practices

By Diego Flammini

Staff Writer

Farms.com

A new platform is available to Minnesota farmers looking to connect with other producers engaged in different farming practices.

The University of Minnesota Extension’s Southwest Regional Sustainable Partnership (RSDP) and Center for Integrated Natural Resources and Agricultural Management (CINRAM) recently released Farmmaps.

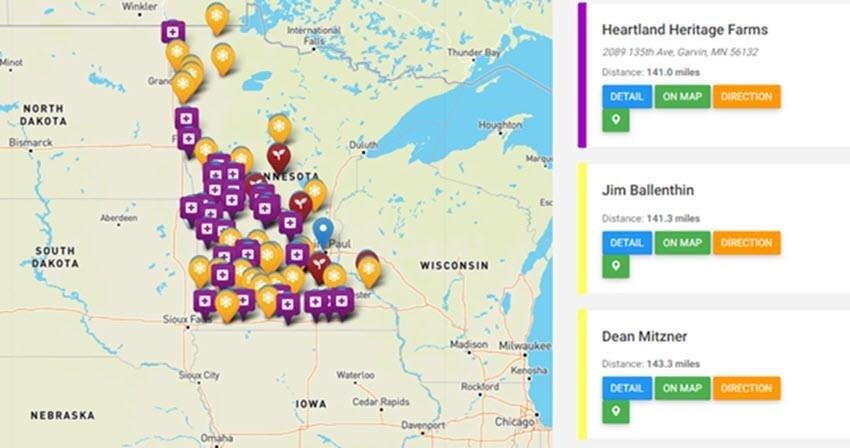

Farmmaps is a free and interactive online tool allowing farmers to create community, network and share case study information.

“We have restaurant maps where you can find a place that’s close by, read a little bit about it and make a decision,” Dean Current, director of CINRAM, told Farms.com. “Farmmaps operates in a similar fashion.”

The online map currently has 45 case studies on it, broken down into three categories:

- Soil health (tillage, cover crops, etc.),

- Silvopasture (combining pasture and trees to provide feed for cattle and opportunities for forest management), and

- Snow fence (the Minnesota Department of Transportation pays producers to leave corn unharvested to prevent snow from blowing onto busy roads.)

More categories could be added in the future, Current said.

To use the map, users can click on a pinned location to learn what practices the individual farm uses and the economic and/or environmental benefits the farmers have experienced. The listings also have contact information should a producers wish to reach out to one another.

Farmmaps screenshot

Jerry and Nancy Ackermann grow corn, soybeans and alfalfa on about 1,200 acres in Lakefield, Minn. They use a blend of no-till, strip-till diversified rotation and cover crops, and their farm is among the case studies available on Farmmaps.

Since the map went live, the Ackermanns have received multiple calls from other producers interested in how they farm.

“Not everyone farms the same way, so it’s great when we’re able to share ideas from one another,” Jerry told Farms.com. “After I’ve given people my recommendations, I tell them to use the app and search out three or four other people.”

And giving farmers the opportunity to speak with one another independently removes bias.

Farmers seeking out information from other places may be getting information that fits what a specific organization is doing.

But communicating farmer-to-farmer ensures producers are receiving honest information, Ackermann said.

“If you go to your local co-op and say you’re thinking about doing strip-till, well the co-op is selling fertilizer so they’re going to push what they sell,” he said. “With the map, you’re talking to people who aren’t selling anything. You’re talking to them about what they’re doing and what they’ve discovered along the way.”

Ackermann, for example, strip-tilled his corn for the last 25 years but last year decided to no-till his corn.

Speaking to fellow producers about no-till gave him the confidence to try it, he said.

“I learned what they did and why, and that gave me the courage to try,” he said. “We had some of the best yields we ever had.”