By Virginia A. Ishler

Production perspective

Dairy operations regardless of size typically utilize pasture for either their lactating or nonlactating animal groups. This strategy can extend forage inventory while providing animals an environment off concrete. However, feeding management practices used for stored feed also apply to pasture, which includes monitoring quality over time. A lot of changes occur from spring through fall including stage of maturity, sward mixtures, and degree of grazing management. There may be a very good explanation why animals are not performing well on pasture that goes beyond heat stress.

In 2018 the Extension dairy team worked with seven organic dairy producers evaluating pasture quality from May through September. The pasture samples were analyzed by wet chemistry through the Cumberland Valley Analytical Lab. The results from this project can be extrapolated to any dairy operation utilizing pasture. There were the typical differences in grazing management practices as well as the diversity of sward mixtures used among the farms.

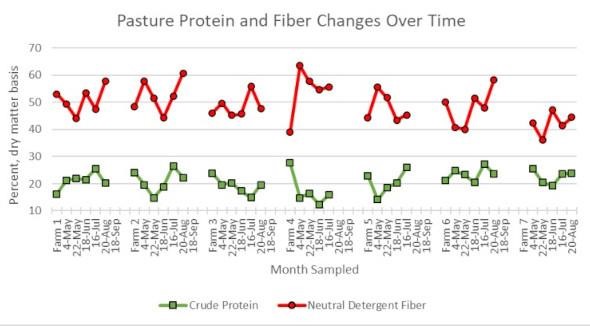

Most farms had six samples taken spanning from May 4 to September 18. Figure 1 shows the changes that occurred in crude protein and neutral detergent fiber. Assuming these pasture changes are typical of any dairy operation, even utilizing some stored feed with pasture, the dramatic changes could have negative effects on milk volume and components. With shrinking margins due to high feed costs and mediocre milk prices, the small investment in pasture analyses to fine-tune protein and carbohydrate balance would pay for itself if production slumps were minimized. Depending on the price per pound of fat and protein, some farms could be losing close to $1.00/cwt for depressed components.

For the dairies utilizing pasture for dry cows and heifers, extreme changes in protein and fiber can have negative results. By not adjusting supplemental concentrates for the changes in pasture quality, body condition and heifer growth can be compromised. This can have long-term implications for the animal’s upcoming lactation if metabolic problems ensue or heifers freshen too small or thin.

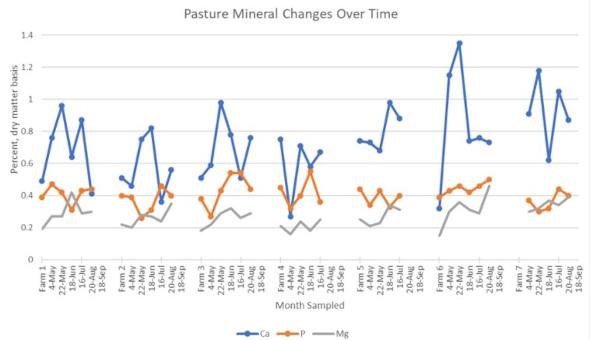

Reproductive performance on many dairies is challenged during the summer. Heat stress gets most of the blame, however, for pastured cows, there may be other factors. Figure 2 shows the fluctuations in mineral content over the season. Calcium and phosphorus changes are substantial and imbalances in these minerals can contribute to less than stellar pregnancy rates. This could also be an issue for breeding age heifers.

Metabolic problems in dry cows that relate to minerals can be partially explained by pasture mineral changes. Milk fever, retained placenta, and displaced abomasum might be impacted by not adjusting supplementation properly to match the changing mineral levels. The one mineral that remained constant throughout the grazing season was potassium. It stayed over three percent on a dry matter basis regardless of stage of maturity or sward mixture.

Pasture quality changes coupled with inadequate quantity could make a bad situation worse. Rainfall is usually plentiful in the spring and fall to support a sward height necessary to meet the animal’s need for intake. However, during the summer when temporary droughts occur, then pastures may be more like dirt lots. Implementing good grazing management practices regardless of the animal group can provide a lot of benefits. If pasture quality is not monitored then precision feeding is not being realized and there are potential negative impacts to animal performance and health, which ultimately affect cash flow.

Figure 1. Changes in crude protein and neutral detergent fiber on pastures from seven organic dairy farms.

Figure 2. Changes in calcium, phosphorus, and magnesium on pastures from seven organic dairy farms.

Economic perspective

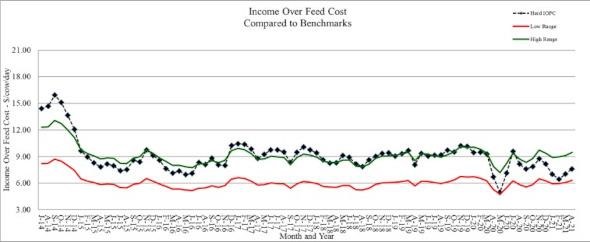

Monitoring must include an economic component to determine if a management strategy is working or not. For the lactating cows, income over feed cost is a good way to check that feed costs are in line for the level of milk production. Starting with July 2014’s milk price, income over feed cost was calculated using average intake and production for the last six years from the Penn State dairy herd. The ration contained 63% forage consisting of corn silage, haylage and hay. The concentrate portion included corn grain, candy meal, sugar, canola meal, roasted soybeans, Optigen and a mineral vitamin mix. All market prices were used.

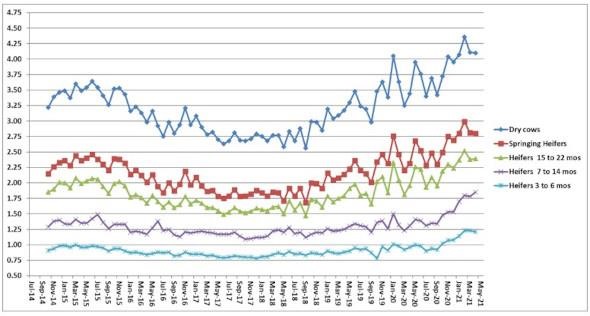

Also included are the feed costs for dry cows, springing heifers, pregnant heifers, and growing heifers. The rations reflect what has been fed to these animal groups at the Penn State dairy herd. All market prices were used.

Income over feed cost using standardized rations and production data from the Penn State dairy herd.

Note: April’s Penn State milk price: $18.77/cwt; feed cost/cow: $8.18; average milk production: 84 lbs.

Feed cost/non-lactating animal/day.

Source : psu.edu