By Erika Machtinger,Hayley R. Springer

Many species of tick can be found on livestock and horses in Pennsylvania. These ticks can cause physical harm to animal hosts and transmit pathogens causing diseases.

Control of important ticks affecting livestock and horses includes recognizing important species, removing ticks, and preventing and controlling ticks in the environment.

What ticks are likely to be found on livestock and horses?

While there are over 20 species of ticks in Pennsylvania, only a few are pests of livestock and horses. Most of these ticks are three-host ticks, meaning they bite a different animal during each of their three life stages, larva, nymph, and adult. Usually, these ticks choose progressively larger animals for each life stage. This means that adult ticks are the most common life stage found on livestock and horses. However, occasionally nymphs will be found as well.

Blacklegged tick (Ixodes scapularis)

Also known as the “deer tick,” this species is very common throughout Pennsylvania. Adults are active in the late fall and early spring.

PATHOGENS: This species can transmit the pathogens that cause Lyme disease to susceptible animals, including horses, and Anaplasma phagocytophila, the cause of equine granulocytic anaplasmosis. Cattle, sheep, and goats are not susceptible to Lyme disease infection and in the U.S., do not experience disease related to A. phagocytophila.

Blacklegged tick adult female

Lone star tick (Amblyomma americanum)

Lone star ticks are found in the southern and southeastern parts of Pennsylvania. Adults and nymphs are around in the spring and early summer. It can be found mostly in the coastal plain but is also found in the piedmont. The larvae, called seed ticks, prefer humans.

PATHOGENS: Though this tick can carry pathogens that can cause disease in humans, they are not considered a major vector for diseases of horses and livestock.

Lone star tick adult female

American dog tick (Dermacentor variabilis)

American dog ticks are found throughout Pennsylvania. Appear as adults in late spring and summer. While dogs are the preferred host of the adult, but it has been recorded on numerous wild and domestic animals as well as man.

PATHOGENS: This tick may cause annoyance to domestic livestock, but it is not a known vector of pathogens causing disease in livestock or horses. However, American dog tick bites can cause paralysis in livestock, people, and dogs.

American dog tick adult female

Winter tick (Dermacentor albipictus)

Winter ticks are commonly found on forested ungulates like deer and elk throughout Pennsylvania. However, it will also feed on domestic animals if given the opportunity. It is a one host tick, completing its entire life cycle on a single host so all life stages may be present on large animals.

PATHOGENS: This tick can transmit the pathogen that causes anaplasmosis in cattle. Though historically this disease has not been a major concern in Pennsylvania, recently, large animal veterinarians have been seeing more cases of bovine anaplasmosis.

Asian longhorned tick nymph

Asian longhorned tick (Haemophysalis longicornis)

This species is invasive to Pennsylvania and has been recovered from the central and eastern counties. In its native range in Asia, this species prefers cattle as hosts. Unlike our native ticks affecting livestock and horses, this tick is parthenogenic (females can reproduce without a male) and all life stages may be found on large animals. In the United States, this species has been recovered primarily from deer, sheep, cattle, and other ungulates although also from domestic pets and people. This tick is known to carry a pathogen that causes anemia, ill-thrift, and even death in cattle. Recently, this pathogen was identified for the first time in the U.S. in cattle in Central Virginia, an area where the Asian longhorn tick has been found in high numbers. In areas of severe infestations this tick can greatly reduce milk production in dairy cows and may even cause animal death.

Why should I control and remove ticks?

Ticks can transmit pathogens and cause other physical problems to animals. Ticks cause local irritation to skin which may result in hair and blood loss from rubbing on trees and fences. Secondary infections may be present in these open wounds. Heavy infestations of ticks may cause losses to physical condition in cattle including weight loss and anemia and reduced milk production. Horses are also susceptible to Lyme disease and equine granulocytic anaplasmosis and cattle to bovine anaplasmosis. Saliva from certain tick species can also cause tick-bite associated paralysis. In addition, many ticks in Pennsylvania found on livestock and horses will also bite other animals, so handling animals with tick burdens may increase the risk of bites to humans and pets.

Where should I look for ticks on my animals?

Once a tick has located an animal host, they will identify a suitable area to bite. While ticks can be found anywhere on the body, usually, ticks select areas that are warmer and more protected with thinner skin like the chest, under the jaw, flank, underbelly, mane, ears, dewlap or brisket area, or elbow. In many cases there is a local skin reaction that can be felt as a small lump.

How do I remove a tick from my animal?

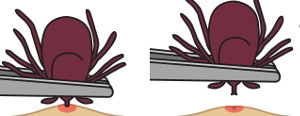

Should you find a tick on your animal, it should be removed immediately. Tick removal from animals is the same as with people. It is important to not crush or squish the tick as the tick may regurgitate potential pathogens into your animal through the bite which may increase the risk of pathogen transfer. In addition, do not apply any agents to the tick like oils, petroleum jelly, heat or fire, paint, nail polish remover, or similar. Using a sharp pair of forceps or tweezers, the tick should be grasped as close to the skin as possible and removed slowly straight away from the skin. Ticks can be placed in a small plastic bag in the freezer and saved for future pathogen testing if desired.

Using sharp tweezers or forceps, grasp the tick close to the skin and pull slowly straight away from the bite.

How to I prevent ticks from getting on my livestock or horses?

Tick prevention starts in the environment and is aided with on-animal control methods. Pasture modifications can be made to reduce contact animals have with wooded perimeters where ticks are often found. Moving fence lines 10 feet from the edge of the woods and keeping vegetation in those corridor areas mowed short and free of debris can prevent tick movement towards pastured animals. Eliminating brush and woody debris like fallen branches from the perimeter of pastures can reduce small mammal habitat which in turn reduces immature tick hosts. Because ticks are susceptible to drying out, they are not found in sunny areas with low cut grass. Mowing grasses in pastures and reducing weeds eliminates suitable sites for ticks to search for hosts, and cutting overhanging branches to allow sunlight can reduce humidity which can help dry ticks out and kill them. It is not necessary to chemically treat pastures for ticks. However, if pastures include wooded edges, these areas can be treated with acaricides to reduce tick presence.

If possible, animals should be checked for ticks frequently. For horses in areas at risk for tick bites, daily is recommended as the pathogen that causes Lyme diseases can transmit in a little as a day. As ticks are often small before they feed, thoroughly checking animal skin with both hands and eyes may be more effective than eyes alone.

Pyrethroid products such as permethrin or cypermethrin wipe-on or spray repellents, shampoos, dusts, ear tags, pour-on products, or similar applied to animals can be helpful. However, many topical treatments are not meant for extended protection and generally last 4-8 hours. These products also do not guaranteed prevention of tick bites so checking animals for ticks should be continued even with application. Make sure that all products used are labeled for use for the animal they are intended for and follow all label application, safety, and disposal instructions.

Fence lines bordering wooded habitat can put livestock and horses at risk for contact with ticks. Moving the fence line away from the wooded or brushy habitat can reduce risk of tick contact.

Trimming overhanging tree limbs and removing understory brush and debris seen here along the fence line can reduce suitable tick habitat and reduce tick bite risk.

If you have questions or concerns regarding tick-borne diseases it is recommended to contact a large animal veterinarian. If you have questions about tick identification, please contact the Insect Identification Laboratory at Pennsylvania State University.

Source : psu.edu