By Steve Burak, Kathy Baylis, and Jonathan Coppess

Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics

University of Illinois

In the last couple of weeks, we have seen several more maneuvers in President Trump’s ongoing trade war, including the addition of a new front—India. On June 15, India announced it was placing import tariffs on 28 U.S. products, including almonds, apples, pears, chickpeas, and various steel products (

Goel, June 15, 2019). This move stems from President Trump’s March 2018 steel and aluminum tariffs, in which he placed import duties of 25% on steel and 10% on aluminum from most major exporters to the U.S. (

Swanson, March 1, 2018).

India had initially announced a list of retaliatory targets last June, however, they have held off on implementation while trying to negotiate a trade deal. These tariffs come on the heels of President Trump deciding to strip India of trade privileges under the Generalized System of Preferences (GSP) (

Swanson and Goel, May 31, 2019). The

GSP is a U.S. trade program which is aimed at helping the developing countries climb out of poverty by eliminating duties on thousands of products from 120 designated countries (

USTR). And India—the most significant program beneficiary—had seen over $5 billion worth of goods qualify for duty-free import each year.

India’s announcement comes just a week after the President dropped his threat of a 5% tariff on all Mexican imports after claiming to have reached a deal with Mexico on immigration enforcement. In the announced deal, Mexico negotiated a 45-day window to demonstrate that their own measures to slow the flow of migrants would work, and an additional 45-days to discuss a bilateral agreement with the U.S. on returning migrants if the measures aren’t working (

Shear, June 11, 2019).

The suspended threat of a Mexico tariff is good news for U.S. agriculture, as Mexico would most certainly target agricultural products in retaliation. As we have written before, U.S. agriculture is routinely in the cross-hairs when countries choose the products to target in response to trade disputes (farmdoc daily,

October 4, 2017). Mexico is no exception, having targeted U.S. agriculture in the wake of the 2009 NAFTA trucking dispute, and again in response to President Trump’s steel and aluminum tariffs—which have recently been removed from Mexico and Canada (

Levine, Behsudi, and Rodriguez, May 21, 2019). And in response to the threatened tariffs, Mexico had already prepared a list targeting goods from agricultural states. While the details of the list haven’t been made public, the one thing we know is corn—Mexico’s top U.S. agriculture import—would have been excluded from retaliation (

Reutters, June 5, 2019).

While the Mexico announcement is good for U.S. agriculture, India’s implementation of tariffs is not. India is increasing tariffs on 28 U.S. imports, amounting to $1.4 billion worth of goods. The primary items affected are almonds and apples, hitting California—the world’s largest almond producer—and Washington state, respectively. Apples will see a 70% duty (

Iyengar, June 17, 2019), while almonds will see their duty increased 20% (Goel, 2019). Additionally, the duty on walnuts will increase from 30% to 120%, chickpea duties increase to 70% from 30%, and lentils will have a 40% duty (

Hindu Business Line, June 16, 2019).

India and its population of 1.3 billion people are one of the largest and fastest growing economies in the world. India ranks as our ninth largest trade partner in goods, with $87.5 billion in two-way trade in 2018, and also ranks as our 13th largest goods export market (

USTR, April 8, 2019). Goods exported to India were up 31% from 2017 to $33.5 billion in 2018, and agricultural exports totaled $1.5 billion—making India the U.S.’s 18th largest agricultural export market (USTR, 2019).

Despite the increase in exports, the U.S. still runs a trade deficit with India, a major sticking point with President Trump. Trade (in goods and services) with India in 2018 totaled $142.1 billion, with exports of $58.9 billion and imports of $83.2 billion—a deficit of $24.2 billion. Trade in goods represents $21.3 billion of the total deficit, while services account for roughly $3 billion (USTR, 2019).

The deficit with India isn’t all bad news. Our goods deficit with India had been growing over the last ten years, due to increasing imports and stagnant exports. However, in the last three years, exports to India have been increasing at an increasing rate. Exports increased 31% in 2018, after an 18.5% increase in 2017. And as of April 2019, exports are on track to surpass 2018’s high of $33.5 billion worth of goods.

When it comes to agricultural exports, the top commodities sent to India are tree nuts, cotton, fresh fruit, and dairy products. Tree nuts are the top export, at $662 million in 2018, with fresh fruit coming in second, accounting for $163 million (USTR, 2019). So, it’s no surprise India is targeting top U.S. agriculture export commodities, similar to China going after soybeans.

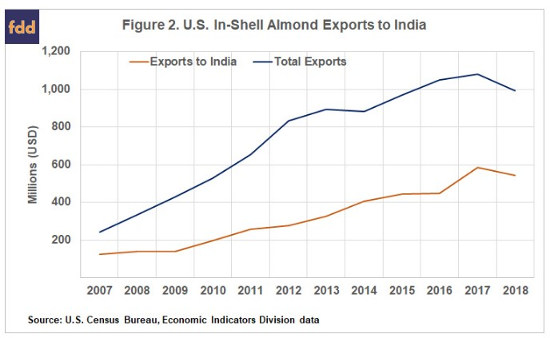

An increase of duties on almonds is undoubtedly going to affect California growers. India is by far the largest buyer of U.S. almonds, buying over $543 million worth of the in-shell variety in 2018—roughly 55% of all U.S. in-shell almond exports. Additionally, the Indian market for U.S. Almonds has increasingly grown larger the last ten years, from a market share low of 32% in 2009 to last year’s high of almost 55%. Exports of in-shell almonds have also grown over 292% from 2009’s low of $138 million. And as of April 2019, India had already purchased $192 million worth of almonds or 77% of all U.S. in-shell almond exports.

India is also an important export market for U.S. apples, importing $158 million worth of fresh apples in 2018, second only to Mexico’s $284 million. The $158 million imported in 2018 represented a record high over the last 20 years and a 63% increase over $97 million in 2017. While not growing at the rate and volume of almonds, apple exports have seen a major jump in the last couple of years, with 2017’s near-record high being a 53% increase over 2016.

Concluding Thoughts

As the number of fronts of the trade war expands to India, a couple of things become clear. First, agriculture continues to be caught in the cross-fire; farmers suffer first and most when retaliatory tariffs are imposed by some of our largest trading partners. Second, the targeting of agriculture isn’t going away any time soon. India is just the latest to mount a defense to the President’s war at the expense of U.S. agriculture. As such, the addition of India to this war on trade will further hurt some U.S. farmers in the short-run and potentially have long-run consequences.

India has emerged as a growing U.S. marketplace, especially for agriculture, with an increase of exports over the last several years. Similar to China and Mexico—who were initially seen as emerging U.S. marketplaces and grew into our first and third largest trade partners respectively—India holds real potential as a future export market. This potential is unlikely to be realized, however, if the U.S. is seen as an unreliable partner and is effectively shut out of the market because of tariffs. The lack of potential access to 1.3 billion consumers would be a major blow to U.S. exporters in its own right; in the wake of the conflicts with Mexico and, especially, China the damage could be profound and long-lasting.