By Danielle Smarsh and Erin Orr

Introduction

Stomach (or gastric) ulcers are a common concern for equine caretakers. Stomach ulcers occur when the stomach lining is damaged by stomach acid. While stomach ulcers are most common in racehorses, all horses can potentially suffer from ulcers, including horses that are in light exercise or rarely exercised. Nutritional management is a key piece of the puzzle when managing ulcers. Several feed management practices can be put into place to help horse owners better manage their horses’ ulcers and decrease the risk of future ulcer development.

Gastrointestinal Ulcers

Equine Squamous Gastric Disease (ESGD) is a specific type of ulceration that can occur in a horse’s stomach. Ulcers can also occur in the glandular portion of the stomach and in the hindgut; however, these types of ulcers have different causes, treatments, and management recommendations, and will not be discussed in this article. Clinical signs of ESGD include poor body condition, weight loss, clenching/grinding of teeth, and colic. Some horses may even display changes in eating habits and behavior such as decreased appetite and sensitivity in the back or girth area. Ulcers can also affect a horse’s overall performance, with horses suffering from ESGD underperforming in competitions. Equine Squamous Gastric Disease is common and is diagnosed in 11-90% of adult horses, depending on which population of horses is studied. Ulcers are more common in horses that partake in heavy exercise such as racehorses and Olympic level competitors with a prevalence rate ranging between 90-100%. While ulceration rates are lower, ulcers have also been found in 11-59% of pleasure horses (which are not considered to be in heavy exercise). This highlights the potential welfare concerns for horses with ESGD and implies how this could have an economic impact due to underperformance of the equine athlete and cost associated with treatment.

Stomach Anatomy

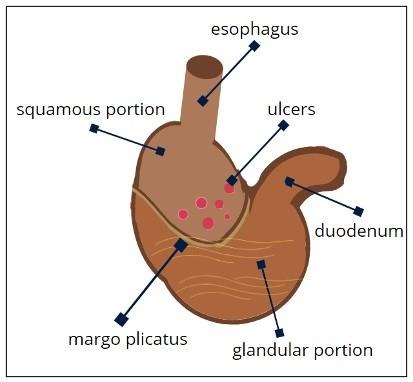

In order to explain how stomach ulcers can develop, let’s first talk about equine stomach anatomy (Figure 1). The horse’s stomach is an essential step in feed digestion, ensuring that nutrients can, later on, be absorbed in the intestines. In order to begin the breakdown of feed before it exits to the duodenum, the stomach secretes acid from the glandular (lower) portion of the stomach. The cells present in the glandular portion are different from the cells that line the upper portion of the stomach. The acid-secreting cells in the glandular portion of the stomach also secrete mucous, creating a layer to protect the cells from the acidic stomach environment. In contrast, in the upper portion of the stomach, known as the squamous (or non-glandular) portion of the stomach, cells do not secrete stomach acid or mucous. Because the squamous portion of the stomach does not produce a mucous protectant, it is susceptible to acid damage. Dividing the glandular and squamous sections of the stomach is a structure called the margo plicatus. The margo plicatus is a visible line that marks where the stomach lining changes from the squamous to the glandular portion. Most often, ulcers develop in the squamous portion of the stomach along the margo plicatus.

Figure 1. Anatomy of the horse's stomach. Developed by Erin Orr, Penn State.

Acid Damage and Ulcer Development

Since the upper squamous portion of the stomach does not secrete mucous to protect itself from stomach acid, acid damage can occur leading to ulceration known as ESGD. Unlike humans who only secrete stomach acid when a meal is ingested, horses continuously secrete stomach acid throughout the day. Saliva contains an important buffer, bicarbonate, which helps to neutralize the stomach acid, but this is only secreted in a healthy horse while they are chewing. For example, if a horse is only fed twice a day, then they may run out of forage in between meals and while acid is still being secreted in the stomach, no saliva is being produced because the horse is not eating anything. Thus, no buffer is sent to the stomach to help protect the squamous section. Therefore, the timing between meals should be kept in mind when feeding horses.

Horses that are fed diets high in sugar and starch (such as high-grain diets) have an increased risk for ulcer development. These starches are rapidly fermented by resident microbes in the gastrointestinal tract and produce acid byproducts which make the stomach environment even more acidic. Furthermore, grains (both textured and pelleted) do not require as much chewing as forages, leading to smaller quantities of saliva produced for a shorter amount of time. So not only will the ingestion of grains produce a more acidic stomach environment than forages, but they also do not cause as much secretion of saliva to help buffer the stomach.

Ulcer Diagnosis

The only way to be sure ulcers are present is to have a veterinarian perform a gastroscopy (Figure 2). This process involves a camera that can be placed in the gastrointestinal tract via the nostril. Horses are usually fasted before this procedure to ensure most surfaces within the stomach can be observed. This process helps veterinarians see if ulcers are present and allows them to give the ulcers scores based on overall ulceration severity (Figure 3, 4). Below is a table of how squamous ulcers are scored within the stomach with grade 1 ulcers being mild and grade 4 ulcers being the most extensive.

Table 1 Scoring system of squamous ulcers used in the United States and in Europe (American Association of Equine Practitioners).

| Grade | Squamous Mucosa Description |

| 0 | The epithelium is intact and there is no appearance of thickening. |

| 1 | The mucosa is intact, but there are areas where the epithelium is thickening. |

| 2 | Small, single, or several distinct lesions. |

| 3 | Large single or extensive superficial lesions. |

| 4 | Extensive lesions with areas of apparent deep ulceration. |

Figure 2. A) A horse with a nasogastric tube and endoscope placed within the nose. B) The screen next to the horse shows the image of the horse‘s stomach obtained via endoscope. Photo credit: Laura Kenny, Penn State.

Figure 3. A picture of an endoscope of a healthy horse’s stomach. Photo credit: Danielle Smarsh, Penn State.

Figure 4. A picture of an endoscope of a horse with stomach ulcers. Photo credit: Danielle Smarsh, Penn State.

Treatment of Squamous Ulcers

GastroGard (also known as omeprazole) is the only medication on the market in the United States that is FDA approved to treat squamous ulcers in horses. Omeprazole works to reduce the production of stomach acid by inhibiting a proton pump within the stomach that is responsible for secretion of stomach acid. It is not just a buffer for stomach acid. Usually, a 28-day treatment with this medication is prescribed by a veterinarian. This medication can also be given at half dose (sold as UlcerGard with no prescription required) to aid in the prevention of ulcers. It is important to use GastroGard and not medication intended for human ulcers when treating ulcers in horses because GastroGard has a special coating to ensure that it is not degraded by the time it reaches the small intestine where it is absorbed. While GastroGard is effective, successful treatment and particularly prevention of future ulcers requires nutritional changes as well.

Feeding Practices to Reduce Risk of Squamous Ulcers

While omeprazole will help heal existing squamous ulcers, successful management and prevention of future ulcers requires a combination of both medication and nutritional management. Some nutritional management steps include:

- Feed multiple, smaller grain and/or concentrate meals throughout the day. By rationing the grain into 3 or 4 meals per day, the increased acidity of the stomach that follows a large grain meal can be avoided. When horses eat a grain meal, they do not chew as much and thus not much saliva will be produced to buffer the stomach acid.

- Ensure your horse has constant access to forage. Provide at least 1.5% of a horse’s bodyweight in dry matter (DM) of forage (hay and/or pasture) per day. For example, a 1,000-pound horse should receive at least 15 pounds of forage per day (0.15 x 1,000). Forage requires more chewing and thus more saliva is secreted compared to a grain or concentrate meal. In addition, the long fiber particles form a mat that floats on top of the stomach contents, helping to prevent the acidic layer from splashing up into the squamous section. If possible, a horse should have 24/7 access to forage. By providing forage throughout the day, both the saliva and forage act as a buffer against stomach acid and can decrease the risk of squamous ulcers developing. If free access to forage is not possible, the use of a slow feed hay net can be used as it increases the horse’s time spent foraging and chewing.

- Avoid feeding more than 1 gram of sugar and starch (listed as sugar and starch separately on a feed tag) per kilogram of bodyweight (BW) per meal and 2 grams of sugar and starch per kilogram of bodyweight per day.

- For example, if you are feeding a 1,000-pound horse (about 450 kilograms) then they should receive no more than 450 grams of sugar and starch per meal (450 kg BW x 1 gram sugar and starch) and no more than 900 grams of sugar and starch per day (450 kg BW x 2 grams sugar and starch).

- If the horse is eating a hay that contains 10% sugar and starch (assuming the horse is eating 1.5% of their bodyweight) then the horse is consuming 1.5 pounds of sugar and starch from the hay per day (681 grams/day). This leaves about 219 grams left per day that can be supplied through the grain.

- Let’s say you are feeding a grain that has a combined sugar and starch level of 15%. Every pound of feed will have 0.15 pounds of sugar and starch. If one pound is about 450 grams, then one pound of feed will have 68 grams of sugar and starch (0.15 x 450). This means that the horse should receive less than 3.2 pounds of that grain per day (219/68=3.2).

Other Risk Factors and Management Practices to Consider

Besides nutrition, there are several other factors that affect the incidence of gastric ulcers in horses. For example, intense exercise and stress can increase the risk of ulcers. Racehorses, which are under very heavy exercise and stalled for long periods of time, have been found to have the highest incidence of ulcers. Increasing turnout time may decrease stress and provides horses with the opportunity to graze. Stress can also be caused by changes in management and routine or by transportation and competition. Avoid stressful situations when possible and talk with your veterinarian about medication options during transport and competition. Provide forage during travel and at competitions to encourage chewing and to decrease the risk of acid damage within the stomach. The long-term use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory (NSAID) drugs such as phenylbutazone and flunixin meglumine can also increase the risk of ulcers since these drugs also inhibit the secretion of the bicarbonate mucous within the stomach that protects itself from the acidic stomach environment. Avoid the long-term use of NSAIDs and talk to a veterinarian about alternative pain management strategies.

Nutritional Management is an Important Tool to Manage Gastric Ulcers

While the environment of horses cannot always be controlled, nutritional management typically can be and it is one important piece of the puzzle for ulcer care and prevention. By putting the feed management practices described by this article into place, horse owners can better manage their horses’ ulcers and decrease the risk for ulcers developing.

Source : psu.edu