By Aaron Sanderford

Nebraskans like to complain about the humidity this time of year. But some might not realize that the corn and soybeans that help power the state’s economy are part of what’s making farmers and their customers sweat.

All plants release into the air much of the moisture their roots absorb from the ground. But the weather is muggier in these parts in July and August than it otherwise would be because corn and soybeans release more moisture than most crops.

Those who monitor the impact of that moisture say corn and soybeans make it more humid here because Nebraska and its neighbors grow a lot of both.

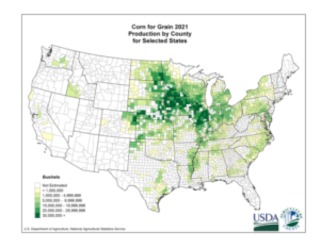

Agricultural experts say corn is being planted more densely across a broader swath of the center of the country. This is where farmers planted the most corn in 2021. (U.S. Department of Agriculture)

Nebraska farmers produced 1.85 billion bushels of corn in 2021, third most in the nation, according to the Nebraska Department of Agriculture. Farmers here raised 351 million bushels of soybeans, good for fourth in the nation.

Corn releases a lot of “sweat”: One acre of planted corn can release up to 4,000 gallons of water a day, she wrote. Soybeans are no slouch, either, she explained. Evaporated moisture from rivers, ponds, lakes and the Gulf of Mexico make a difference, too.

“But the moisture they release into the air does add in a measurable way to the humidity … of more than just the fields,” Boustead said. “People can feel it in cities like Omaha and Lincoln.”

This is where farmers planted the most soybeans in 2021. The plants sweat more moisture than most other crops, trailing corn. (U.S. Department of Agriculture)

State Sen. Curt Friesen grows corn and soybeans on his 1,300-acre farm in Henderson, a town of 991 people southwest of York. He said summertime spikes in humidity are just part of life “when you live out here in the middle of corn country.”

He chuckled at Boustead’s finding that an Iowa cornfield can be muggier than Miami Beach. It’s rough this time of year to change a tire on an irrigation center pivot in the middle of a humid cornfield, where no breeze can reach you, he said.

“You just deal with it,” Friesen said. “It’s just the way it’s always been. I always think it’s more stifling in the city when you’re surrounded by concrete, and the buildings block the wind.”

Al Dutcher, the Nebraska Extension agriculture climatologist, said irrigation plays some role in what’s changing. Federal farm programs and their impact on farmers’ planting choices also have significant influence, he said.

A sweaty corn field in Saunders County, Nebraska, just outside Ashland. (Aaron Sanderford/Nebraska Examiner)

More acres in parts of Kansas, Nebraska and North and South Dakota that used to plant wheat have been shifting toward corn and soybeans. That matters, he said, because wheat reaches its peak point of letting moisture go in the spring and fall.

Because more people are planting corn and soybeans from Texas to central Canada, Dutcher said, the midsection of the United States is seeing more concentrated moisture from crops that release more moisture at the same time of year, in midsummer.

“The reason I’m confident we are seeing more moisture is the expansion of the Corn Belt,” Dutcher said. “Some has to do with farm programs, how they’re set up — and individual producers looking at prices and chasing an opportunity.”

Dennis Todey, who directs the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Midwest Climate Hub in Ames, Iowa, said Iowa and other Midwestern states are used to the humidity spikes of “corn sweats” because they long ago shifted to corn and soybeans.

Soybeans abound in Saunders County, Nebraska, just outside Ashland. (Aaron Sanderford/Nebraska Examiner)

Great Plains states are feeling more of that shift today, he said. “Corn sweats” and the combined effects of a changing climate are making it feel hotter, boosting dew points and the heat index.

Click here to see more...